Indigenous Connections in Physical Education and Wellness: 3 Strategies to Get Started

Summary

In response to the increasing call for a deeper integration of Indigenous perspectives in curriculum, we share our classroom practices to inspire and support the meaningful inclusion of Indigenous ways of knowing in physical education. By aligning our strategies with the Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies, our goal is to enhance the educational experience and well-being of students across Canada. As we work towards decolonizing our classrooms and responding to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action, we have identified three key strategies for fostering a more inclusive pedagogy in physical education, (a) adopting the medicine wheel to communicate classroom expectations, (b) building connections to the land through outdoor teaching and learning, and (c) integrating oral story telling into instructional practice. We hope this article provides teachers with actionable pathways to create a holistic, safe, and inclusive physical education environment that honours Indigenous perspectives.

Main article

When it comes to providing quality and culturally affirming learning opportunities for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, there is a growing demand for a deeper integration of Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing into curriculum and teacher training (Wotherspoon & Milne, 2020). Acknowledging and embedding this into physical education curricula is strongly connected with Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action. Alberta’s Physical Education curriculum is experiencing a significant transformation, shifting from separate Health Education and Physical Education curricula to a combined Physical Education and Wellness curriculum (PEW). In Edmonton, Alberta, we have an increasing number of Indigenous students (Frew, 2022). Many of whom have expressed to us that they feel disconnected from the colonial educational practices and cannot relate the provincial curriculum to their lived experiences or Indigenous worldviews, prompting a need for change in our classrooms.

During the introduction of a Cree game called Tatanka Tatanka in physical education class, a grade 4 Cree student's face lit up. This game, traditionally used to teach children about herding buffalo, served as a warm-up activity. The student eagerly shared her Cree heritage and felt a deep connection to her culture through participating in the game.

The positive experience of our grade 4 students playing Tatanka Tatanka highlighted for us the importance of integrating Indigenous perspectives into our teaching. As PEW teachers, we are committed to embracing the wisdom accumulated over millennia, promoting harmony between mind, body, and spirit, and nurturing culturally conscious and compassionate youth. This article aims to share our classroom practices with other PHE teachers to inspire and support the meaningful integration of Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing into PHE classrooms.

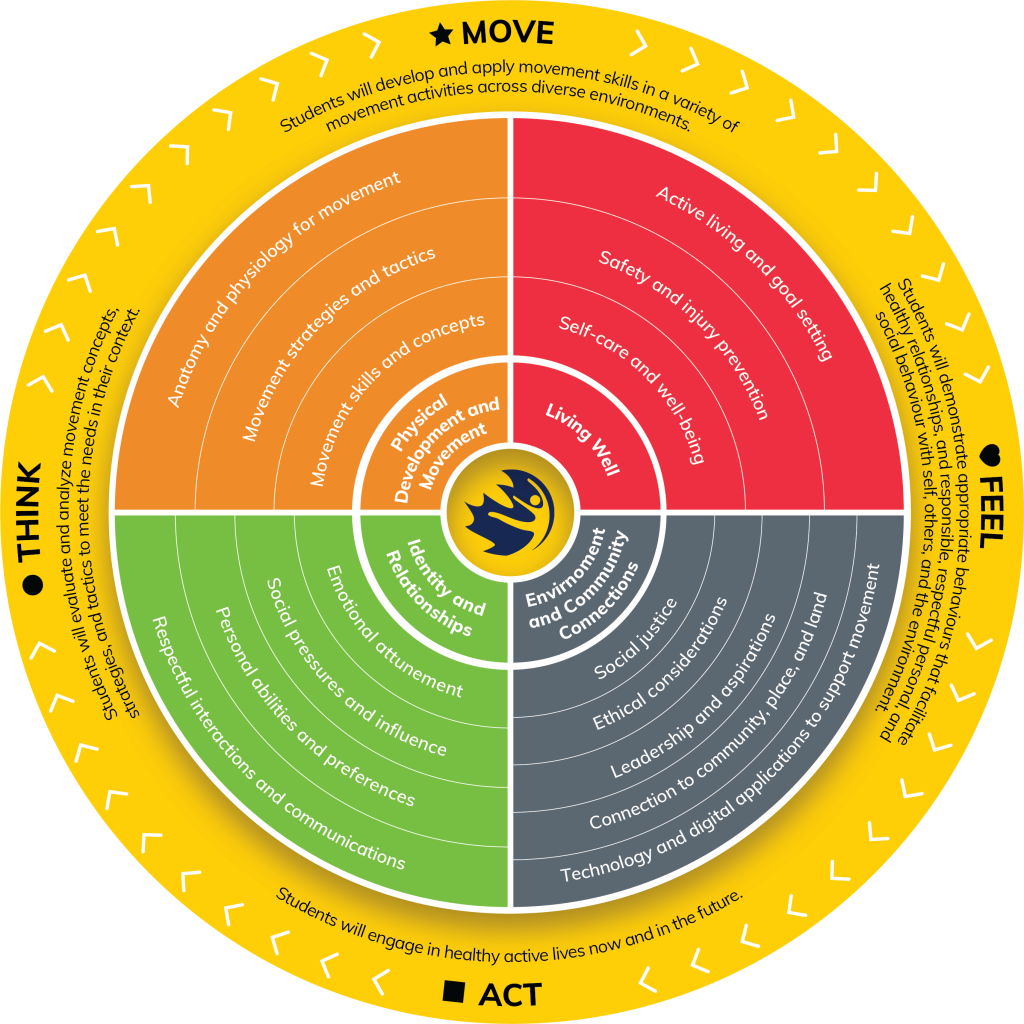

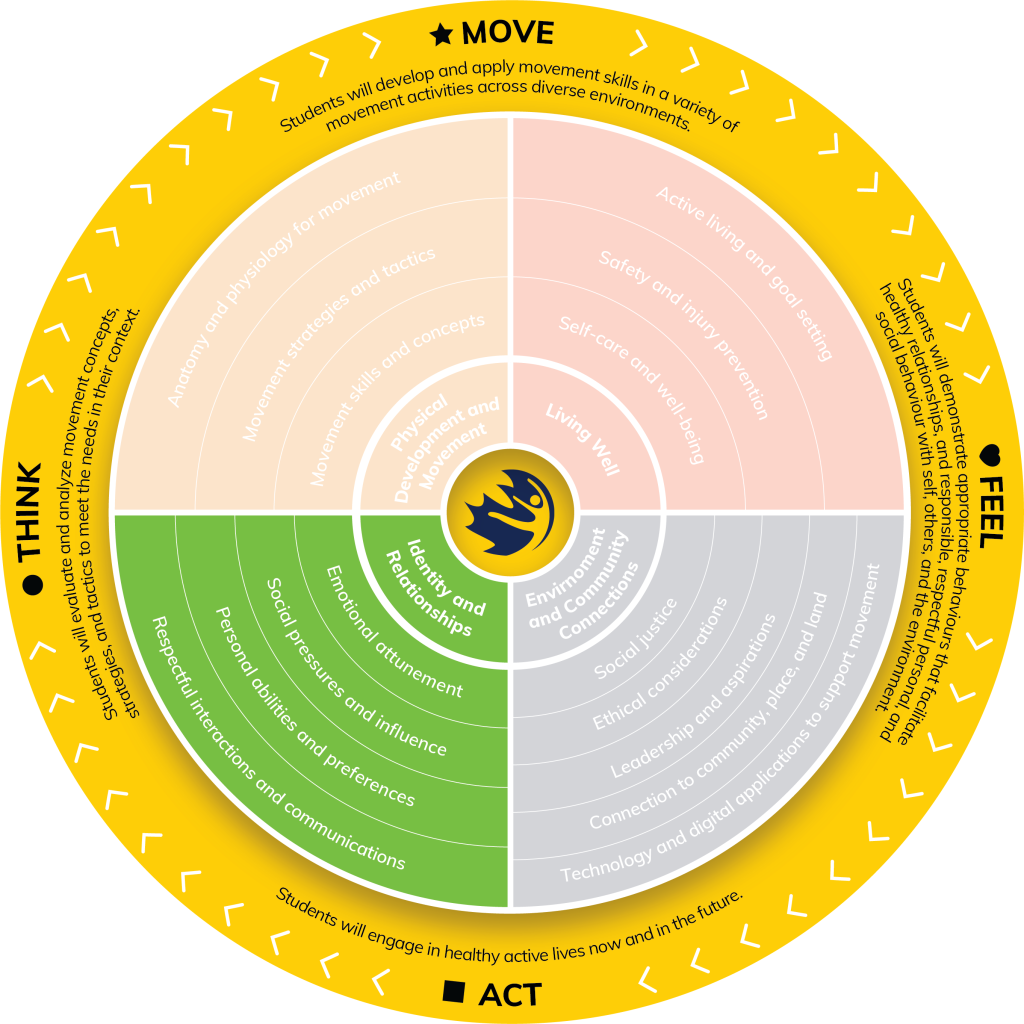

Figure 1: Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies

Physical and Health Education (PHE) Canada, our nation’s long-standing leader in our field, developed the Canadian Physical and Health Education (CPHE) Competencies (Figure 1). They provide all provinces/territories the curriculum competencies and outcomes of sound physical and health education curriculum (Robinson et al., 2021). The CPHE Competencies emphasize the importance of inclusivity, equity, and respect for diverse perspectives, including Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Indigenous content has been woven throughout the Competencies to support young people with quality and culturally affirming learning in health and PE (Davis et al., 2023). By aligning our strategies with these competencies, we aim to support the integration of Indigenous content, thereby enhancing the overall educational experience and well-being for students in Canada.

In our journey towards decolonizing our classrooms and responding to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s (TRC) calls to action, we have identified three key strategies for fostering a more inclusive pedagogy in PEW.

#1 Medicine Wheel

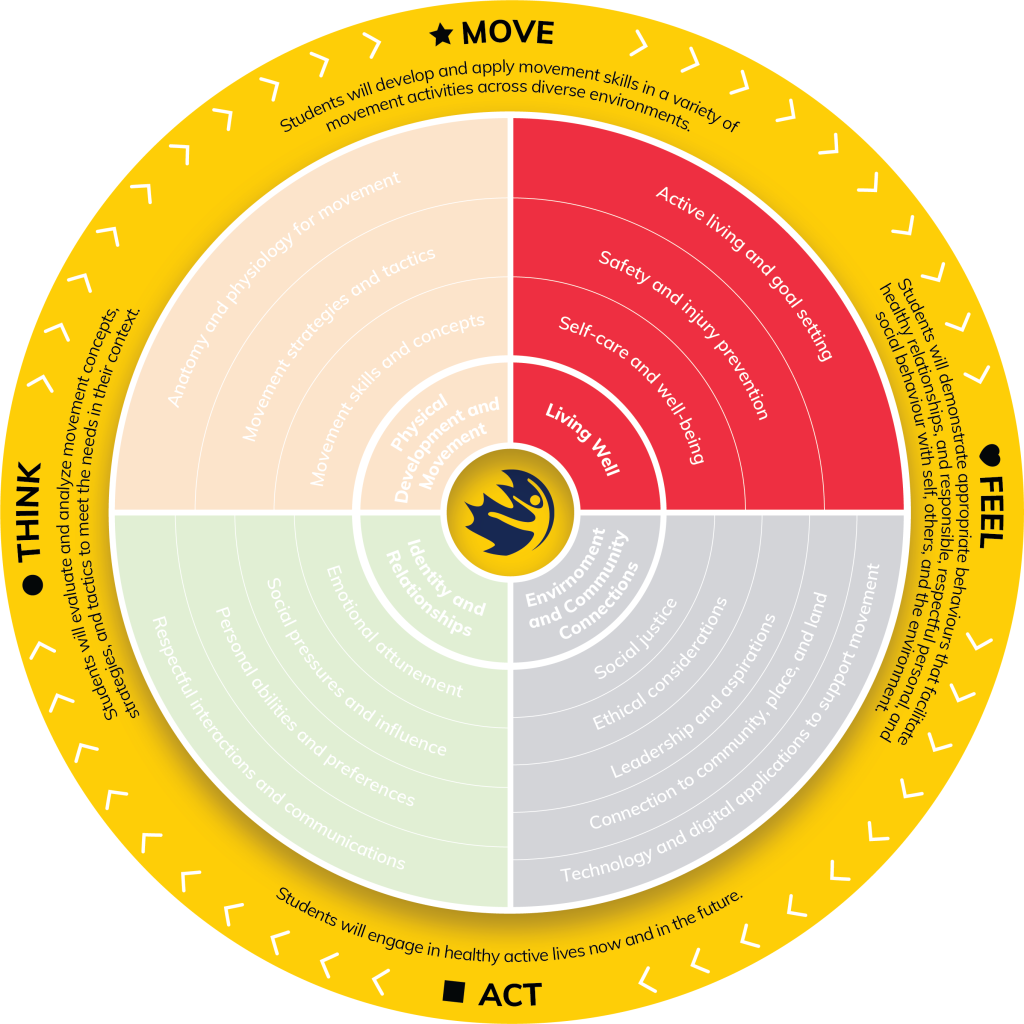

Figure 2: Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies - Living Well

The medicine wheel, rooted, and created, in Indigenous culture, visually represents wholistic health dimensions and life cycles (National Website of Medicine, n.d.). Adopting the medicine wheel to communication expectations and guide reflections related to the “living well” competency, as depicted in Figure 2 (Davis et al., 2023, p. 63) can offer a more inclusive pedagogical approach. Indigenous perspectives on health encompass broader elements of wellness, which differ from siloed Western interpretations (Nesdoly et al., 2020). In Alberta, educational shifts reflect this wholistic approach as we transition from separate PE and Health curricula to PEW (Alberta Education, 2022).

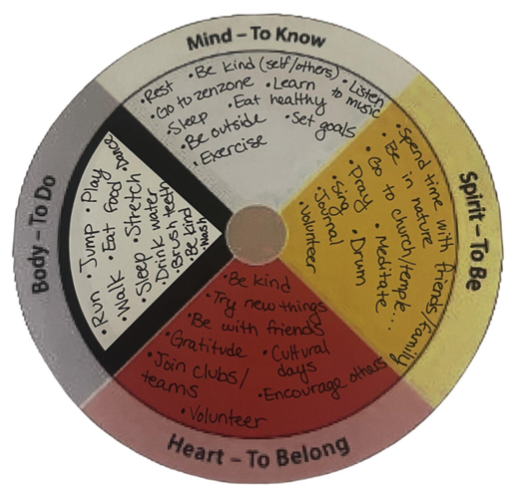

Figure 3: Calgary Board of Education. (2022). Indigenous Education Holistic Lifelong Learning

Central to the medicine wheel is the principle of the Cree word wahkôtowin, explaining the interconnectedness of all relationships (Online Cree Dictionary, n.d.). This concept extends beyond human interactions and encourages respect for all forms of life, including plants, animals, and the land (Campbell, 2005). While the medicine wheel is used differently across Turtle Island, in our classrooms the quadrants represent the mind, body, heart, and spirit, honouring the medicine wheel's representation of balance and growth. It teaches us that a balanced wheel will roll forward smoothly while an unbalanced wheel will falter. By adopting the medicine wheel in our classrooms, we encourage an approach to PEW where each wheel component is given equal importance, ensuring that our students' health is wholistically nurtured.

Grounding the medicine wheel in our classroom expectations fostered a community of learners who respect and care for each other, the environment, and those around them. Rather than creating a list of rules and expectations at the start of the year, our class created a medicine wheel (see Figure 3) to guide all our interactions. The class medicine wheel was revisited throughout the school year to hone in on the wholistic approach to PEW. Our students regularly related their in-class experiences to the areas of the medicine wheel. Throughout the year, we saw their understanding grow as various learnings can be essential to multiple dimensions of the wheel.

#2 Building Connection to the Land

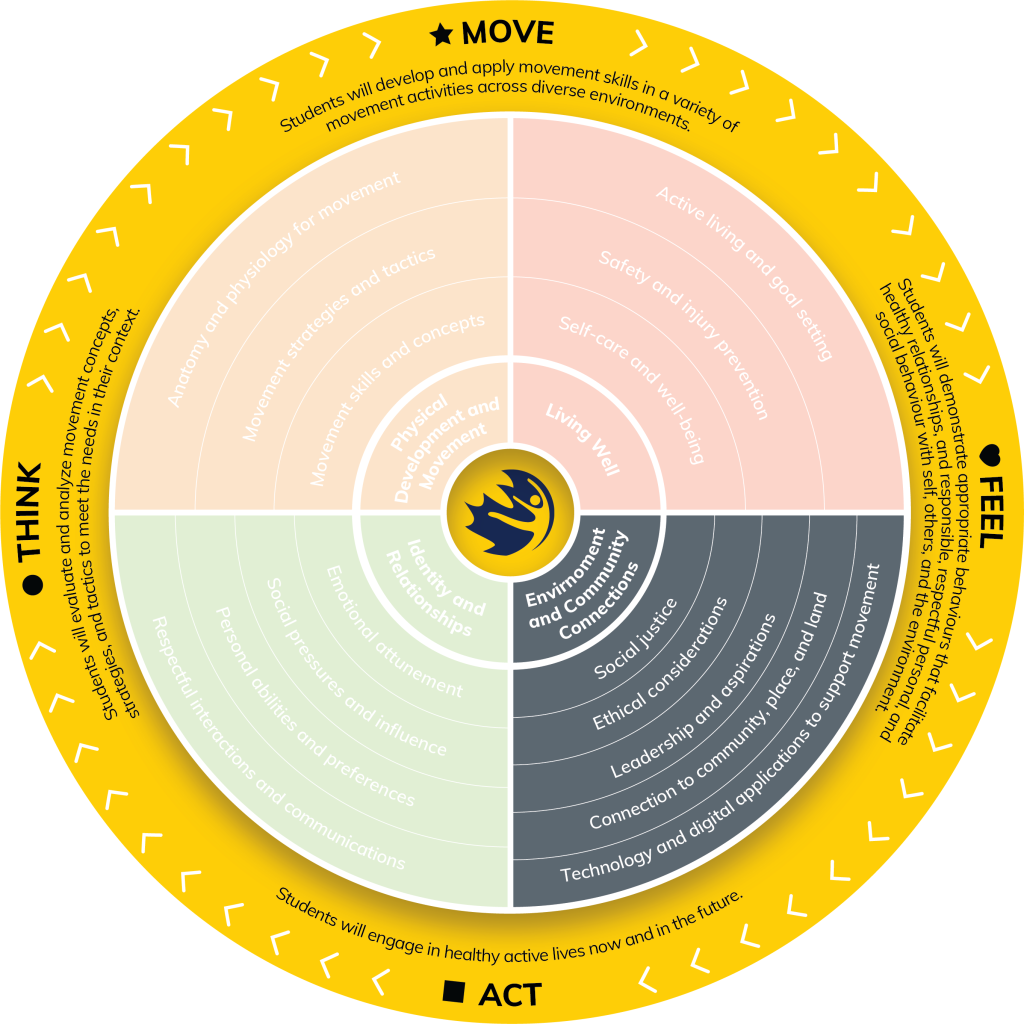

Figure 4: Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies - Environmental and Community Connections

The connection to the land is fundamental in many Indigenous cultures and offers a different PEW learning perspective. Considering the teaching of wahkôtowin, bringing your classes outside is a simple way to begin nurturing this “environment and community connection”, a 'big idea’ in the CPHE (see Figure 4; Davis et al., 2023). Additionally, going outside promotes rich play (Spencer & Wright, 2014) and increased mobility and fitness (Edwards-Jones et al., 2018). Here are some activities you could engage in with your class to build connection and stewardship for the land:

- 6 Ways to Get the Benefits of Mindful Walking

- Meet a Tree

- Spring Cleanup: A Classic Community Builder

- Teaching: Better Orienteering

Figure 5: Land Acknowledgements Collaboratively Developed with Grade 4 Students in Alberta

Exploring the history of the land and its peoples are essential to fostering a connection, appreciation, and respect for our surroundings. To extend these lessons and work towards reconciliation, create land acknowledgments with your class before engaging in recreational activities. Refer to Figure 5 for an example of a land acknowledgement created collaboratively with a grade 4 class in Alberta. This is an important part of Indigenous culture as it “reminds us of the gifts that come from the land and our responsibilities to the land” (Herrera, 2020, p. 8). What is a Land Acknowledgment and Native Land are great resources to help get you started and guide discussion. Before we began this process ourselves, many students did not know why we made land acknowledgments. By the end, they had created thoughtful and informed land acknowledgments that are now regularly spoken at the beginning of class. Throughout the year, we have noticed students: eager to go outside despite weather conditions, being respectful and attentive during presentations from Indigenous knowledge keepers, and demonstrating more stewardship of our school grounds.

Figure 6: Alberta Students Playing a Blackfoot Game called Linetag

Lastly, incorporating traditional games and activities allows for active living outside year-round, especially when indoor space is limited. Figure 6 displays a photo of students playing an outdoor Blackfoot game called Linetag. Here are some resources for games, their histories, and what materials can be harvested respectfully (with proper protocol) from the land to build equipment:

#3 Story Telling

Figure 7: Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies - Identity and Relationships

Indigenous peoples have used storytelling as an educational tool for thousands of years (Chan, 2021). Stories are a form of entertainment and a conduit for history and values while serving as an opportunity to build community and connection (Barton & Barton, 2017). However, throughout Canadian history, we’ve seen a systematic dismantling of Indigenous culture, including assimilation and colonization through recreation and sport (Forsyth & Wamsley, 2006) and devaluing the long-held tradition of oral storytelling (Hanson, 2009). We hope that by incorporating more verbal teachings and sharing of experiences, we can create more inclusive spaces for sport and recreation while providing multiple pathways to building the CPHE competency of “identity and relationship” (see Figure 7; Davis et al., 2023, p. 62).

Figure 8: Title Page for Shi-shi-etko by Nicola L.Campbell

While educational research shows that oral storytelling can improve various students' skills, we see the greatest benefit for PEW in that oral storytelling supports self-exploration and interpersonal skills (Agosto, 2013). We have witnessed how stories, like Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox by Danielle Daniel, allow students to embrace differences in characteristics and physical skills as unique gifts, broadening their worldviews. After reading this book, a grade 4 class at our school happily adapted games for a student with cerebral palsy, leading to greater participation and inclusion. Explicit learning around individual differences eliminated complaints, and these same students regularly volunteer to assist with adapted PEW classes for other students.

Here are some books and related learning topics we have used in PEW to support these learnings:

- Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox by Danielle Daniel - movement patterns and recognizing individual characteristics as gifts

- Shi-shi-etko by Nicola L. Campbell - resilience, connection to the land and importance of family (Figure 8)

- How Coyote Stole the Summer adapted by Stephen Krensky - roles within a team, sharing, and team activities (such as relays)

Additionally, inviting community members to share personal stories during PEW lessons helps promote a culture of “respectful interactions and communication” (Davis et al., 2023, p. 62). Activist and influencer James Jones, also known as Notorious Cree, came to our school to share his gift of Indigenous Dance with the students. His expression of self and Cree culture through powwow dance and honest and vulnerable storytelling captivated the entire school. His visit enriched the students’ understanding of Indigenous art forms, highlighting the connection between physical activity and cultural heritage, sparking interest in students who had previously been resistant to dancing in PEW.

Providing a platform for stories spotlighting Indigenous experiences, voices, or teachings helps students see diverse experiences and perspectives. Not only can this make your classroom a safer, more inclusive space, but it can also cultivate excitement for related activities and games.

Moving Forward

Many teachers recognize the importance of including Indigenous perspectives in their classrooms, but integrating them into practice can sometimes feel daunting or overwhelming. Such hesitation may stem from a need for more understanding or fear of misrepresenting Indigenous perspectives (Milne & Wotherspoon, 2023). By providing the following three concrete strategies for incorporating Indigenous connections, we aim to give teachers the confidence and guidance to continue this vital work:

- Incorporating the medicine wheel;

- Building connection to the land; and,

- Storytelling

It is important to recognize the diverse cultures, histories, and worldviews of Indigenous communities, as such we encourage educators to engage with the specific teachings, practices and traditions of local Indigenous people in their geographical area and within their school community. By grounding education in the unique cultural contexts of the communities' students belong to, teachers can foster more meaningful and respectful leaning experiences that reflect the rich diversity of Indigenous cultures. We hope this article offers teachers a path forward and helps with creating a more wholistic, safer, and inclusive learning environment in PE that honours Indigenous perspectives.

References

Agosto, D.E. (2013). If I had three wishes: The educational and social/emotional benefits of oral storytelling. Storytelling, Self, Society, 9(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.13110/storselfsoci.9.1.0053

Alberta Education. (2022). Physical Education and Wellness. https://curriculum.learnalberta.ca/curriculum/en/s/pde

Barton, G. & Barton, R. (2017). The importance of storytelling as a pedagogical tool for Indigenous children. In S. Garvis & N. Pramling (Eds.), Narratives in Early Childhood Education (pp. 45–58). https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315640549-4/importance-storytelling-pedagogical-tool-indigenous-children-georgina-barton-robert-barton

Calgary Board of Education. (2022). Indigenous Education Holistic Lifelong Learning. https://cbe.ab.ca/about-us/policies-and-regulations/Documents/Indigenous-Education-Holistic-Lifelong-Learning-Framework.pdf

Campbell M. (2005, November 1). Reflections: We need to return to the principles of Wahkotowin. Eagle Feather News.

Chan, A. (2021). Storytelling, culture and Indigenous methodology. In A. Bainbridge, L. Formenti and L. West (Eds.), Discourses, dialogue and diversity in biographical research. European Society for Research on the Education of Adults. (pp. 170–185). https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/49770/9789004465916.pdf?sequence=1#page=185

Davis, M., Gleddie, D.L., Nylen, J., Leidl, R., Toulouse, P., Baker, K., & Gillies, L. (2023). Canadian physical and health education competencies. Ottawa: Physical and Health Education Canada. https://phecanada.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/canadian-phe-competencies-en-web.pdf

Edwards-Jones, A., Waite, S., & Passy, R. (2018). Falling into LINE: School strategies for overcoming challenges associated with learning in natural environments (LINE). Education 46(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1176066

Frew, N. (2022, October 22). Indigenous population in Edmonton area continues to grow, Statistics Canada says. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/indigenous-population-in-edmonton-area-continues-to-grow-statistics-canada-says-1.6624253

Forsyth, J. & Wamsley, K. (2006). ‘Native to native ... we'll recapture our spirits’: The world Indigenous nations games and North American indigenous games as cultural resistance. International Journal of Sports History 23(2), 249–314. https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1080/09523360500478315

Hanson, E. (2009) Oral Traditions. Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/oral_traditions/

Herrera, S. and Centre for Equity and Inclusion (2020). Land Acknowledgement Guide. Sheridan College. https://source.sheridancollege.ca/cei_resources/8

Milne, E. & Wotherspoon, T. (2023). Student, parent and teacher perspectives on reconciliation-related school reforms. Diasport, Indigenous and Minority Education, 17(1), 54–67. https://doi-org.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/10.1080/15595692.2022.2042803

National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). The medicine wheel. Native Voices. Retrieved May 12, 2024, from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/exhibition/healing-ways/medicine-ways/medicine-wheel.html

Nesdoly, A., Gleddie, D. & McHugh. T. (2020). An exploration of indigenous peoples’ perspectives of physical literacy. Sport, Education and Society 26(3), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1731793

Online Cree Dictionary. (May, 2024). Wahkôtowin. Retrieved May 12, 2024, from http://www.creedictionary.com/search/index.php?q=wahkohtowin

Spencer, K. H., & Wright, P. M. (2014). Quality outdoor play spaces for young children. Young Children, 69(5), 28–34.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Wotherspoon, T. & Milne, E. (2020). What do Indigenous education policy frameworks reveal about commitments to reconciliation in Canadian school systems? The International Indigenous Policy Journal 11(1), 1–29. https://roam.macewan.ca:8443/server/api/core/bitstreams/af525ae0-9801-4d52-b6f7-39e97edc4e58/content