Amplifying Student Voice in Physical Education

What is Student Voice? Student Voice refers to the active, meaningful, and authentic engagement of young people in the decision-making processes that affect their learning, lives, and sometimes communities. Student Voice acknowledges that students have unique perspectives on learning, teaching, and schooling, and should have the opportunity to actively shape their own education.

Amplifying Student Voice can be achieved through continuous class consultation and negotiation, designing learning activities that incorporate student interests, and providing opportunities for cooperative learning. Within the context of Physical and Health Education (PHE), Kim Oliver and colleagues describe that an activist approach outlines four key pedagogical features to support Student Voice in PHE (Shilcutt, Oliver & Luguetti, 2024). In combination, these strategies collectively aim to enhance Student Voice and agency while developing the knowledge and skills necessary for lifelong physical activity:

- Student-centered pedagogy;

- Creating spaces in the curriculum for students to critically study their embodiment;

- Inquiry-based education centred-in-action; and,

- Sustained listening and responding over time.

What can Student Voice look like in PHE?

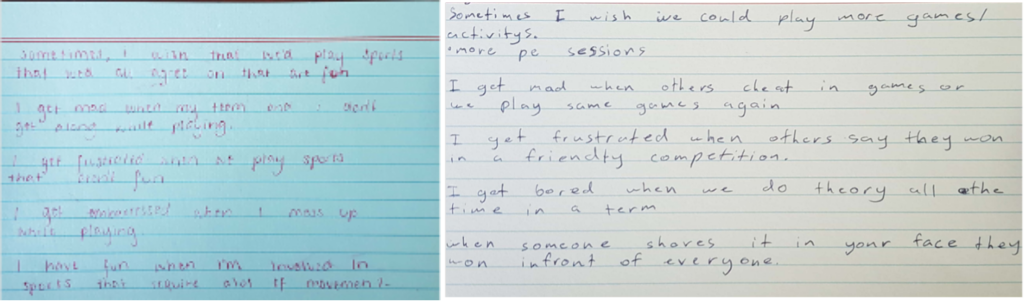

Simple activities with students can help us to amplify their voices and understand their perceptions of PHE. For example, you can ask students to write down their thoughts on PHE or a specific element of it. Free writing tasks that ask students to complete sentences such as the following can prove useful when considering our teaching practice: “Sometimes I wish…”; “I get mad when…”; “I get frustrated when…”; “I get bored when…”; “I get embarrassed when…”; and “I have fun when…” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Perception on PHE – free writing tasks

When listening to Student Voices through free writing exercises, it's essential to create a comfortable and open environment. Activities that encourage students to use their imagination can capture rich data about their perceptions:

- Start by explaining that there are no right or wrong answers, and their honest thoughts and feelings are what matter most.

- Participate in the activity yourself to build trust and share personal experiences.

- Follow their leads, let them go on tangents, and always ask "why" to help them elaborate.

- Use their words when discussing their responses to show you’re genuinely listening.

- You also can ask students to draw and create the best PHE teacher and the worst PHE teacher (see Figure 2).

- In addition to asking them to draw the best or worst teacher, you could prompt them with questions like, "If you could tell PHE teachers two things to make PHE better for people your age, what would you say?"

.png)

Figure 2: The best and worst PHE teacher

These imaginative activities allow students to envision and articulate improvements, providing valuable insights. By asking students to imagine a better PHE class, students can express their ideas and perspectives creatively, leading to more meaningful and actionable feedback.

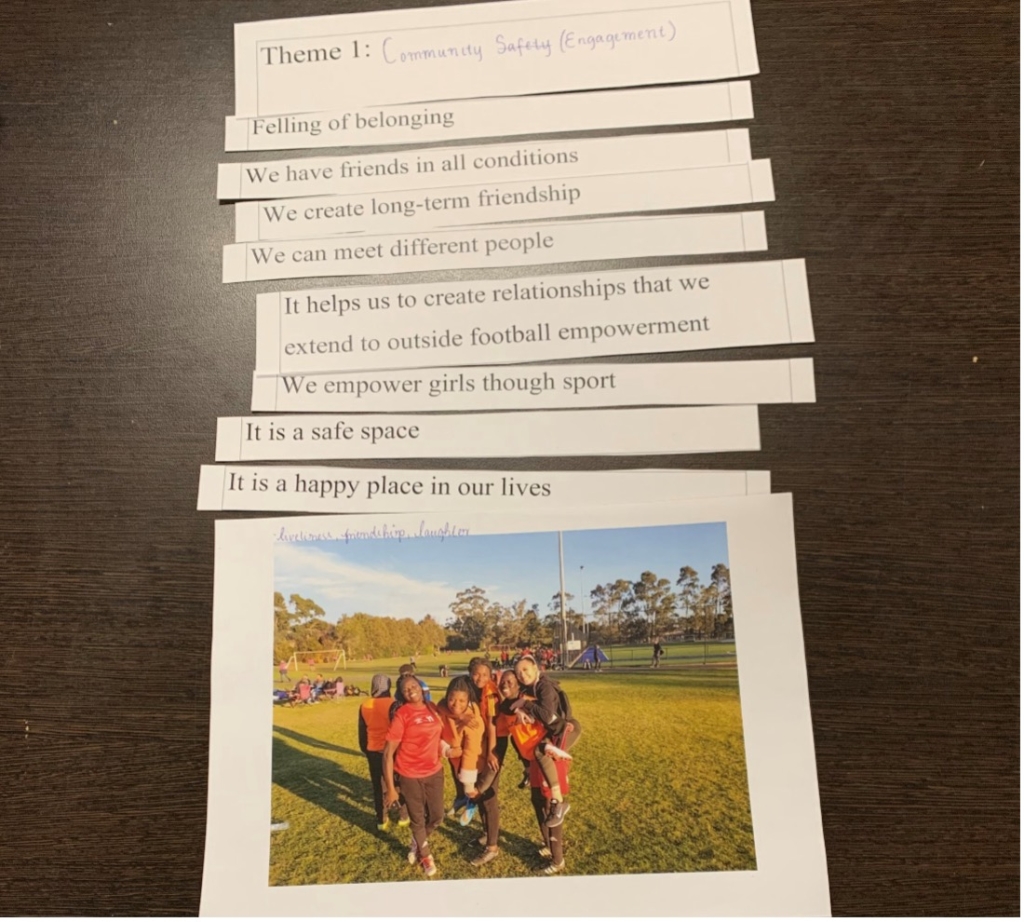

Furthermore, incorporating creative methodologies can greatly enhance how educators listen to Student Voices. For example, try asking students to bring in pictures that represent their feelings about PHE and/or sport. Once they have chosen their images, work together to label them and analyse what these pictures reveal about their experiences and perceptions. This visual approach allows students to express and explore their emotions in a tangible way, providing deeper insights into the role of PHE and sport in their lives (see Figure 3). In addition, the educator and young people could determine common themes such as community safety, sense of belonging and representation in their community sport club.

Figure 3: Photovoice to capture the meaning of Sport - Theme: Community Safety (Engagement)

Why do we need to create space for youth voices in PHE?

PHE programming that prioritizes Student Voice and student-centered learning improves student well-being and sense of belonging because students can see themselves in class, helping them find relevance and meaning (Davis et al., 2023). The Canadian Physical and Health Education Competencies underscore this significance by recommending that all PHE curricula prioritize “Student Voice and Student-Centered” elements. These elements foster empowerment in teaching and learning by offering students opportunities for agency and ownership, supporting the development of life skills and competencies, and assisting with attainment of personal goals and long-term commitment (Davis et al., 2023).

PHE teachers who create opportunities and provide support for Student Voice, contribute to the enhancement of students’ unique perspectives, leading to more relevant and effective solutions in PHE. Furthermore, By including youth in decision-making processes, PHE teachers uphold democratic values, address unique challenges (i.e., inclusion, authentic curriculum and assessment), and harness the potential to drive social change, ensuring that policies and programs are sustainable and beneficial for future generations.

What does an ‘authentic’ youth voice look like in PE?

We understand that achieving a perfect Student Voice is unattainable, but our intentionality should be aimed at seeking an ‘authentic’ Student Voice. Here, we want to share two cases of youth voice in the context of PE. In both examples, we challenged the concept of adultism by creating a pedagogical environment where we did more than just listen; we actively listened and responded over time. In both stories, time and reflection were central components of our approach.

Case 1 - YPAR as a tool for Student Voice – Carla Luguetti

For over a decade, I, Carla, have been dedicated to researching and amplifying young people's voices through Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR). My work is rooted in the principles of activism and social change, drawing inspiration from Paulo Freire's concept of praxis—combining action and reflection to identify, critique, and address social injustices. This journey has been one of continuous self-reflection. Initially, I struggled to appreciate the full value of young people's voices, often prioritising the perspectives of coaches and theoretical frameworks. Over time, I've come to recognise the limitations of my earlier approaches and constantly question whether my work was genuinely participatory or inadvertently tokenistic. This introspection drives me to strive for authentic collaboration and co-design in sport programs, ensuring that young people's voices are truly valued and heard.Nowadays, students are co-authors of some of my publications as I’ve been working with students as co-researchers in co-design research. For instance, I conducted a project in a charity organisation's African Australian football program in Melbourne, Australia. A sixteen-week YPAR involved young African Australian women and aimed to improve their health and well-being while developing youth leaders. The young women were involved in all aspects of the research, from training in research co-design and YPAR to implementing the program.

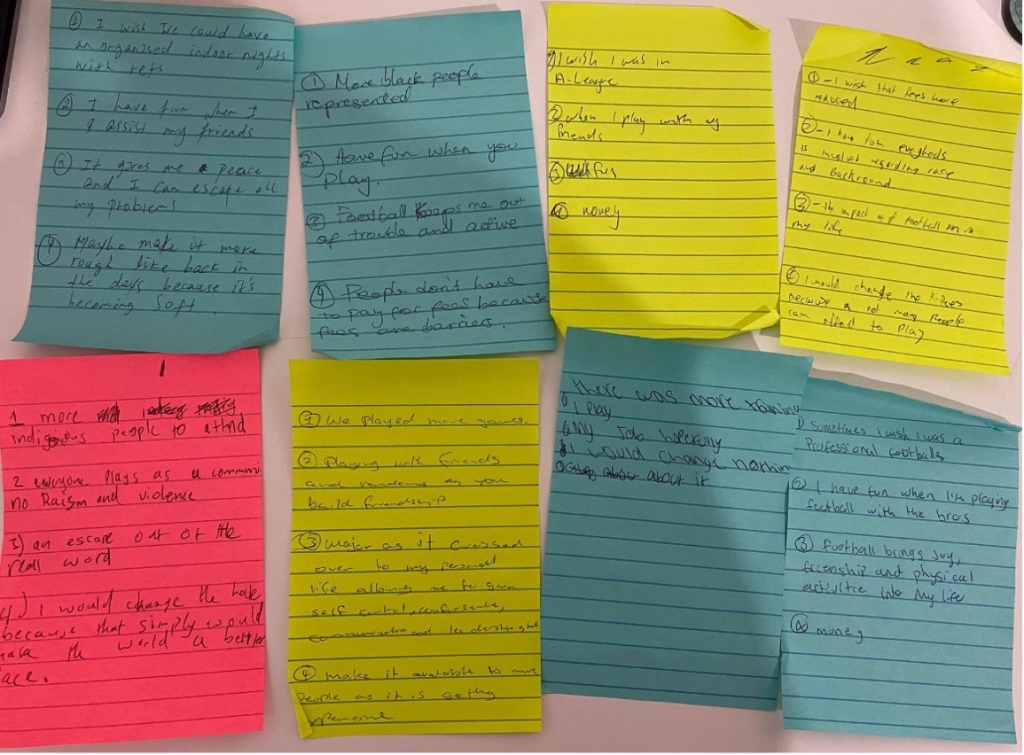

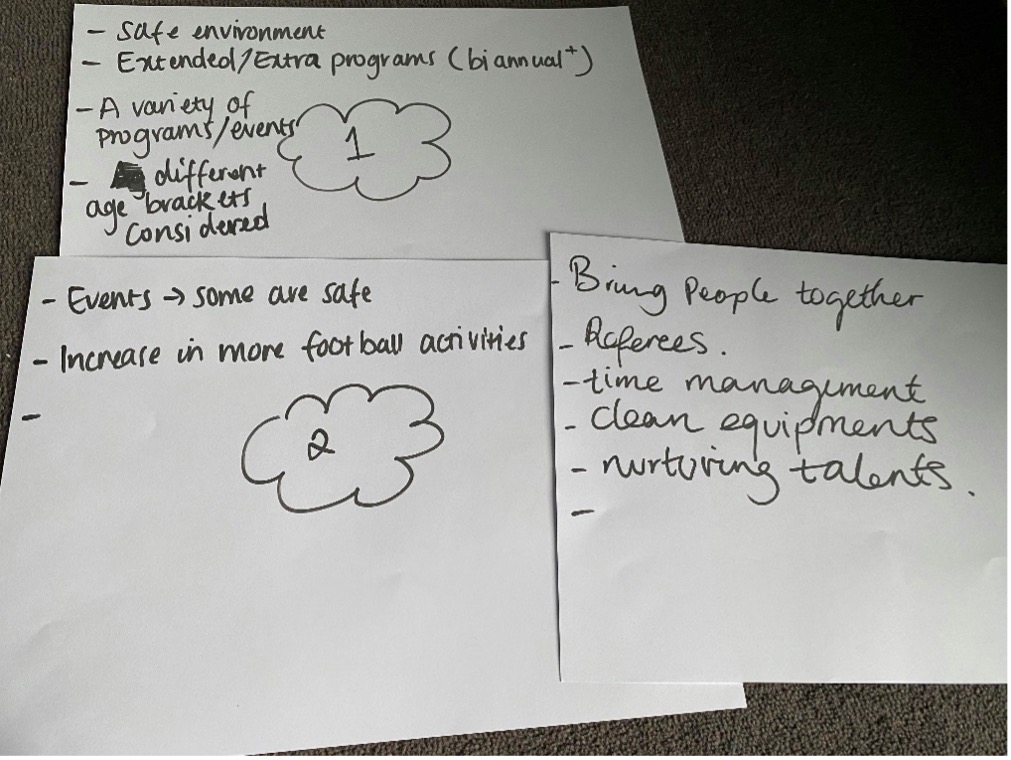

The initial phase focused on preparing the young women for YPAR, discussing its meaning, and co-creating the program's logic. This cyclical process included identifying what facilitated and hindered engagement in the football program and addressing barriers to participation. For example, the young women and I worked with free writing to inquire younger boys in the program in terms of their perceptions:

Figure 4a: Perceptions of the sport programme – free writing

Figure 4b: Perceptions of the sport programme – what they like (1) and what they would like to change (2)

Engaging young women in YPAR has highlighted essential skills such as:

- Authentic listening to young people to plan for change;

- Finding creative and flexible ways to build relationships;

- Navigating the messiness and uncertainty of the research process; and,

- Improving problem-solving skills to respond effectively to young people's needs in their communities.

I conclude this study by emphasizing that YPAR can foster the development of critical capacities in youth studies, nurturing skills and knowledge related to social justice, activism, and democracy, rather than focusing solely on traditional training and predefined practical skills.

Case 2 - Co-designing fitness testing - Laura Alfrey

I, Laura, was working with PHE teachers and students from one Secondary school. The school regularly used fitness testing (i.e., multi-stage fitness test) as the main way to teach about fitness. Fitness testing can be valuable, but in this school, it was taught in ways that made some students feel anxious and judged. These feelings were a consequence of practices such as posting fitness test results on the wall, and whole-class beep tests where attainment is very visible. So, we (Laura and their PHE teacher) did the following:

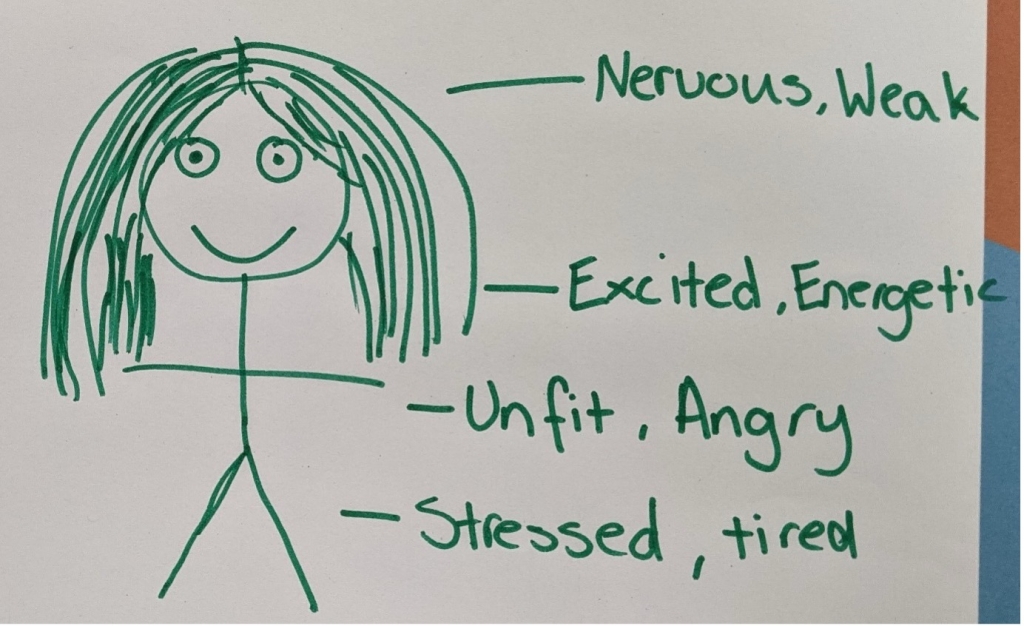

1) Asked the students how they felt BEFORE the fitness testing (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: How one student felt before fitness testing.

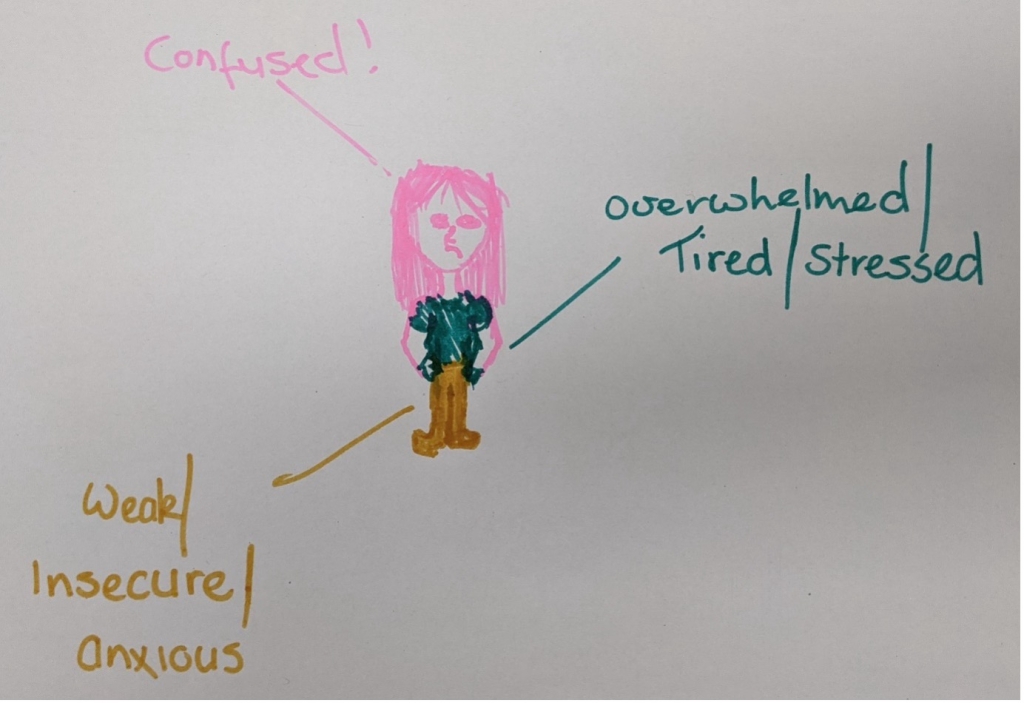

2) Asked the students how they felt AFTER the fitness testing (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: How one student felt after fitness testing.

3) Invited the students to suggest new ways of teaching and learning through fitness testing, that would reduce feelings of anxiety and judgement.

Collectively, the suggestions included students:

- choosing where they are tested, ideally in an area of the school away from the rest of the class;

- choosing who they are tested with, with most preferring to self-test with a few chosen friends;

- choosing which tests they participate in;

- knowing the purpose of fitness testing generally, and each test in particular;

- being clear on the learning that should be taking place;

- knowing the results will not to be published or shared.

These changes were put in place by the PHE teachers. Having their suggestions enacted by their teachers was important because it explicitly demonstrated to the students that their voices had been heard, valued and acted on. Creating opportunities for students to make decisions that impact their learning is important because it can help them co-create PHE that is more meaningful, inclusive.

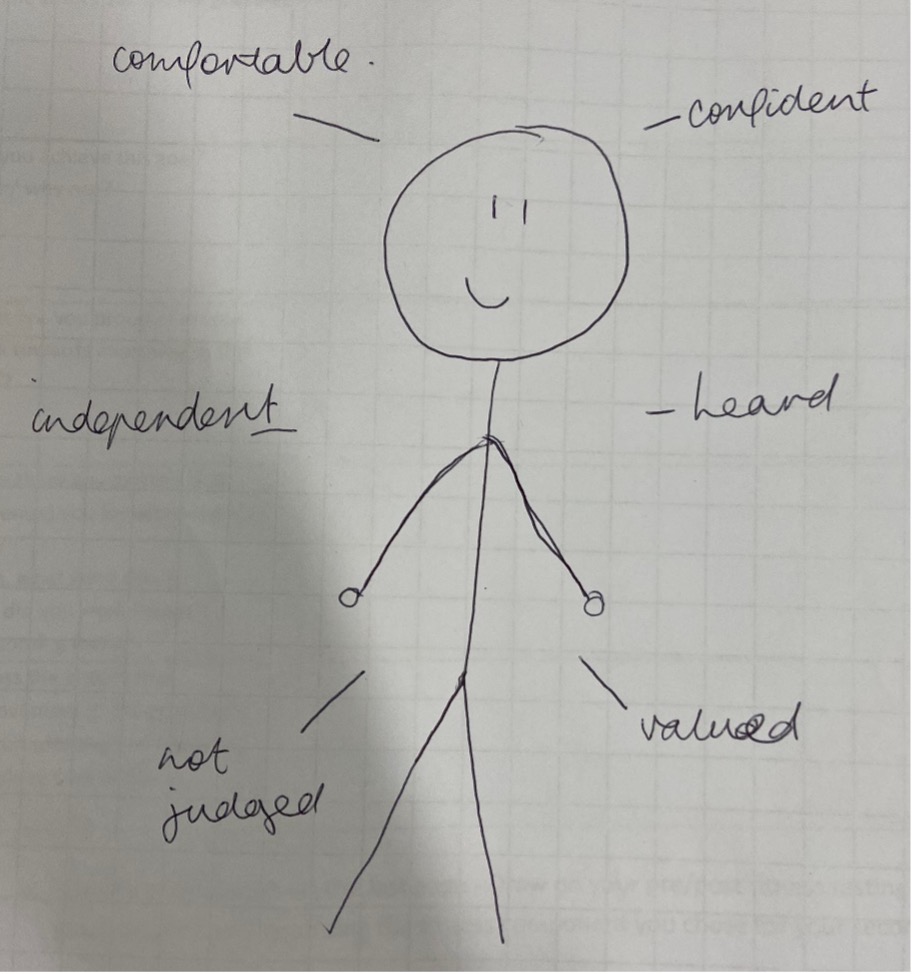

After the students experienced the new approaches to fitness testing, two key things happened:

- Students felt less judged.

- Students felt more valued and heard.

Combined, these changes led to greater engagement, comfort, and enjoyment in PHE classes, especially those that focused on Fitness Testing (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: How one student felt about their ideas about fitness testing being put into action.

Overall, the process of co-producing new approaches to PHE – in this instance fitness testing – took time and care, but it led to meaningful changes to how the students experienced PHE.

Top Key Takeaways

- Challenging Adultism: Student Voice is radical as it challenges "adultism"—the belief that adults always know best. Overcoming this mindset is crucial for fostering fair relationships and inclusive practices, enabling young people to contribute meaningfully to decisions that affect them.

- Beyond Listening: Responding to Student Voice: Student Voice involves more than just listening; it requires meaningful responses and actions based on what students share.

- Building Relationships and Time Investment: Effective Student Voice initiatives require teachers to build strong relationships with students. Time is crucial for fostering trust and honesty in sharing perceptions.

- Reflecting on Positionality: Authentic Student Voice demands that teachers reflect on their own positionalities. Understanding who they are and why they want to listen to youth voices is essential for genuine engagement.

Recommended Additional Resources:

- #AIESEPConnect - Activist Approach to Physical Activity: International Perspectives

- How student voice and agency can transform fitness testing into fitness education

- Academic article - An expansive learning approach to transforming traditional fitness testing in health and physical education: student voice, feelings and hopes

- Working with young women to co-design sports programs

- Academic article - ‘Sitting there and listening was one of the most important lessons I had to learn’: critical capacity building in youth participatory action research

- PHE Canada’s Student-Centered Learning Toolkit for Engaging Students in School-Based Initiatives – A for Youth by Youth Approach

References

Davis, M., Gleddie, D.L., Nylen, J., Leidl, R., Toulouse, P., Baker, K., & Gillies, L. (2023). Canadian physical and health education competencies. Ottawa: Physical and Health Education Canada.

Shilcutt, J.B., Oliver, K., & Luguetti, C. (Eds.). (2024). An Activist Approach to Physical Education and Physical Activity: Imagining What Might Be (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/b23165