“The Peer Mentorship Network Helped Me Flourish”: A Whole School Approach to Peer Mentorship

Abstract

Health promoting schools is a holistic approach to school health that considers the social and physical environments within and outside of school that impacts student health (Turunen et al., 2017). Schools play an important role in adolescent mental health, yet whole school approaches to mental health promotion are underutilized, underfunded, and not well understood (Langford et al., 2015). When an effort is made to improve adolescent mental health within a school setting, the focus often trends toward service delivery and treatment for illness rather than population-based initiatives (PHAC, 2017). This paper describes the practices of Health Promoters working for Mental Health and Addictions at Nova Scotia Health and their experience supporting a whole school approach to peer mentorship at a high school with a population of 800+ students. Even though the Peer Mentorship Network adopted a whole school approach, there was a trend for students to confuse the role of the peer mentor with one-on-one counsellor. Students needed to be re-engaged and reminded about the purpose of the initiative. Evaluation was ongoing, and the Health Promoters provided considerable support to help health promotion champions working in schools. Health Promoters can consider building networks within and outside of school settings to support whole school approaches. Activities engaging the entire school were better received than educational sessions about specific topics. Researchers could consider studying other mental health initiatives that use a whole school approach.

Keywords: peer mentorship; health promoting schools; whole school approach; Nova Scotia; flourishing

Introduction

Background

Schools play an essential role in the mental health of adolescents (Pulimeno et al., 2020). In the 1980s, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the Health Promoting Schools (HPS) framework, a wholistic approach to school health considering the role of the broader social and physical environments within and outside schools on student health (Turunen et al., 2017). This shift from a more traditional approach, which focused solely on delivering health education to students, aimed to create a positive culture shift within schools (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). Yet, despite the investments in HPS, a systematic review by Langford et al., (2015) found that while the WHO framework effectively improved some aspects of student health (i.e., reduced alcohol use and prevent violence), the overall effects on mental health were limited. One potential reason for this finding is that the assessed outcomes for mental health promotion in schools were illness-focused (i.e. depression) instead of health-focused (i.e., flourishing) (PHAC, 2017).

In Canada, adolescent self-perceived mental health has been steadily declining, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Findlay & Arim, 2020). Canadian adolescent (ages 12 – 17) self-reported mental health as “excellent” or “very good” decreased from 77.9% to 62.3% from 2015 to 2021. Self-reported mental health as “fair” or “poor” increased from 4.1% to 11.9% during the same period (Statistics Canada, 2023). This means that more adolescents are reporting their mental health as either “fair” or “poor” and less are reporting their mental health as “excellent” or “very good”.

Given the current state of adolescent mental health, there is a need to study health promotion approaches specific to improvements in adolescent mental health. This paper will explore the lessons learned from using a whole-school approach for implementing a peer mentorship network for supporting adolescents’ mental health within a local high school in Halifax, NS. We define mental health as a continuum, with fulfilled mental health as flourishing and incomplete mental health as languishing, as does Westerhof & Keyes, (2010). Flourishing describes a state of high social and emotional health and fulfillment, while languishing describes the absence of good mental health and stagnation (Keyes, 2022).

Peer Mentorship

One commonly used program studied and implemented within schools is peer mentorship. Peer mentorship is "the emotional and practical support between two people who share a common experience, such as a mental health challenge or illness" (Peer Support Canada, 2023). Sometimes referred to as cross-age mentorship programs, a traditional peer mentorship model in schools allows peer mentors, through training and adequate supervision, to provide student peers with one-on-one support and mentorship in personal development, decision-making, and life transitions (Noll, 1997).

Peer mentorship shows positive results with goal setting, accountability, and communication skills, providing opportunities for self-reflection (Petosa & Smith, 2014). A cross-sectional study by Karcher (2009) compared school connectedness amongst adolescents serving as a peer mentor vs. a control group, finding positive statistically significant differences in the peer-mentor group for school-based outcomes (i.e., school connectedness). Similarly, a qualitative study by James et al., (2014) looked at the mentors' experiences, reporting that peer mentors experienced “becoming grown-ups” as they nurtured and mentored younger students. It suggests that peer mentorship benefits both the mentees and the mentors.

Traditional models of school peer mentorship involve one-on-one counselling. However, there may be barriers to the implementation of this traditional model. For example, some students may never seek a peer mentor, especially given the stigma around mental health and substance use. Additionally, traditional peer mentorship programs may face limitations in volunteers and resources given that one peer mentor can only help so many students. Lastly, it is possible that the school environment itself is unhealthy (i.e., lacking social connection) and requires change, which individual peer mentorship programs do not address. The use of peer mentorship to influence the health and well-being of a whole school has yet to be understood. This brings us to our practice question: How can peer mentorship influence the mental health of an entire school?

This paper describes the formation and implementation of a whole school approach to peer mentorship and its influence on adolescent mental health. The Peer Mentorship Network (PMN) detailed in this report took a new peer mentorship approach, utilizing students as change agents in the school setting to create social and physical environments where all students can flourish and rebuild connections. This paper describes the experiences of Health Promoters working for Mental Health and Addictions at Nova Scotia Health (NSH) (from now on referred to as Health Promoters) and their experience providing support to a local high school with a population of 800+ students to improve school mental health. NSH is the provincial health authority providing health services to over 1 million residents (Nova Scotia Health, 2022; Statistics Canada, 2019).

Context

Over the years, Youth Health Centre Coordinators (YHCC) and Health Promoters have partnered within schools to support health promotion initiatives and improve student health for the HPS Model. A historical article by Kontak et al., (2023) describes the narrative accounts of HPS in the province, from its initial adoption by government in 2005, to its present state known as Uplift, a school-community-university partnership. The Health Promoting Framework includes: 1) teaching and learning, 2) services and programs, 3) health promoting policies, and 4) improving school environments. Health Promoters have traditionally provided support on a case-by-case basis when schools reach out and have engaged students in shaping their environment and school culture.

The first iteration of the PMN, U-knighted for Health, was a youth health action team led by the YHCC that promoted physical and mental health in the school community through various school-wide activities and initiatives. Although the U-knighted initiative was popular among students, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively shifted school culture due to public health restrictions and rolling school closures, making students feel isolated and disconnected (Caldwell et al., 2021). This shift, and the graduation of many students involved with U-knighted for Health, led to the erosion of momentum and the group's ultimate disbanding; however, instead of completely letting go of the once popular initiative, the YHCC decided to look at reinventing the youth health action team and used the new student population as a fresh start.

The Peer Mentorship Network

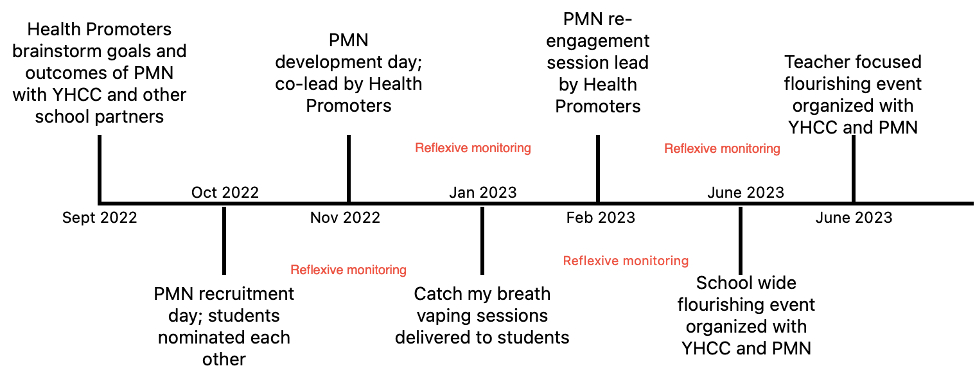

Figure 1. Timeline of the PMN initiatives from September 2022 – June 2023

Laying the Groundwork

Partnerships are an essential component of HPS. The Health Promoters have a long partnership and collaboration with the YHCC, staff, and administration. The principal invited the Health Promoters to facilitate workshops at two staff Professional Development (PD) days in April and December 2022, focused on enhancing student and staff mental health. Through these workshops, Health Promoters aimed to motivate staff to act on creating conditions for flourishing at the school. Overall, the workshops were well-attended and positively received by staff and administration. These PD sessions were also used to introduce staff to the language and activities that would become crucial in developing a PMN. See Figure 1 for a timeline of the PMN activities.

Forming the Network

In September 2022, Health Promoters offered to support the YHCC and other school staff with creating a student PMN to strengthen school mental health, particularly for grade 9 students who, as reported by the YHCC, often struggle during their first year of high school. Rather than targeting the grade 9 students with a one-on-one peer mentorship model, Health Promoters suggested taking a whole school approach to peer mentorship to support the mental health of all students in all grades.

Health Promoters met several times with the YHCC and other school partners, acting as dedicated health promotion champions, to conceptualize the goals and outcomes of the PMN and support program implementation. A recruitment day was held where Health Promoters visited the classrooms of students in grades 11 and 12 (accompanied by the YHCC) to promote the PMN and encourage students and teachers to nominate others to become part of the PMN. The criteria for nomination were simple: kind, compassionate students who wanted to lead mental health initiatives for their school. Forty-nine nominations came in via Google Forms, demonstrating initial excitement and enthusiasm for involvement. Many students were surprised and elated that their friends and teachers had nominated them.

Health Promoters facilitated a half day of skills development in the school library for the nominated students. The team engaged with youth about health promotion, how to increase flourishing and decrease languishing, the importance of values, and creating safer spaces and safe people. Students who participated were highly engaged. Of the original forty-nine nominations, forty students agreed to continue participating in the PMN following the skills development day. PMN meetings were held semi-regularly with the participating students, led by the YHCC, to begin brainstorming mental health initiatives. See Appendix A for a step-by-step guide on this experience.

Network in Action

The Peer Mentorship Network met throughout the 2022-23 school year to plan and action mental health initiatives. They agreed on two initiatives, one in the first semester and the second at the end of the school year. See Table 1 for further details.

For the first initiative, only a few members of the PMN volunteered (due to comfort level with facilitation) to plan and facilitate the grade nine sessions on vaping. This initiative required support from grade nine healthy living teachers for delivery of the sessions during class time. PMN facilitators reported mixed reactions from grade nine students, with some being minimally engaged. In contrast, others were engaged and excited to talk to older peers about substance use and other topics.

For the second initiative, those PMN members who did not participate in the first initiative were re-engaged and enthusiastic about planning a whole school initiative, called the Flourishing Event. The event was to take place in one afternoon.

Six activity stations were set up in the gym where students could compete against each other in physical activity challenges, such as axe throwing, chair racing, and hopscotch with a twist. The PMN led the Flourishing Event from planning to facilitation, including holding a rehearsal over lunch hour to ensure the Flourishing Event would run smoothly. They also engaged a youth DJ and MC to make the Flourishing Event fun. Students enjoyed the event; it was an excellent tool for recruiting new members to the PMN.

Table 1. Description of the Peer Mentorship Network (PMN) initiatives and the students impacted.

| Initiatives of PMN | Students Impacted | What they Did |

| Forming the PMN | Grade 11 and 12 | Students nominated each other to join the PMN |

| Health education sessions on vaping | All grade 9 Healthy Living classes | Facilitated discussion and activities (adapted from Catch My Breath (Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH), n.d.)) with grade 9 classes |

| Whole school event for mental health | All students in grades 9-12 | Planned and implemented activity stations in the school gymnasium |

That’s a Wrap

Following the success of the whole school event, the PMN was invited by the school principal to host a similar event for the teachers and staff during a PD Day, allowing the PMN to further build relationships with school staff and promote the group's ongoing activities.

Health Promoters held a final meeting with the PMN to discuss their overall feedback on the process and learnings from establishing the high school’s first PMN. Feedback from students was primarily positive, with some rating the experience 10/10. It was clear that the planning and implementation of the final event helped to re-invigorate the PMN. The YHCC contributed a fair amount of effort supporting student activities, which required infrastructure, budget and supply management, and motivating students; but, found this "manageable" to support the PMN initiatives. Therefore, when the YHCC was asked to compare the initial vision to the result, the YHCC rated the overall experience 7/10 due to the amount of effort and resources required.

Learning and Implications

We summarize our practice implications according to the HPS model. The PMN took a considerable amount of partnerships, time, and support to implement effectively. Every event, including the formation of the PMN itself, was an opportunity to build trust, relationships, and increase understanding of mental health throughout the school. These learnings come from our process and end-of-program evaluation. We used student feedback, one-on-one debriefing, and team discussions to gather our evaluations. Themes for key learnings were discussed amongst Health Promoters and organized based on the Nova Scotia HPS Framework. See Table 2 for further details.

Table 2. Key learnings about the peer mentorship network using a whole-school approach

| Partnerships | Social Environments | Learning and Evaluation |

|

|

|

Partnerships and Readiness

Partnerships were essential for forming and sustaining the PMN. Health Promoters had a pre-existing partnership with the YHCC; this meant the partners were familiar with each other's roles and built trust during past activities. After establishing new partnerships with school administration (i.e.., the principal) and other school staff, Health Promoters met regularly with them to discuss and envision a PMN. Receiving support from frontline practitioners and administration meant that the PMN had buy-in and support from multiple partners. This aligns with the study by McIsaac et al., (2017) who found that collaborative partnerships beyond the school facilitated school health promotion. This is echoed by the WHO & UNESCO, (2021) who promote partnerships beyond education and with stakeholders across sectors (i.e.., public health, mental health and addictions).

The readiness level and support from the administration and the leadership of the YHCC helped the PMN succeed. The YHCC was able to tap into key relationships in the school to create allies for the PMN. For example, the librarian allowed space for activities, the School Council attended the skills day, resource teachers and Educational Program Assistants supported initiatives, and teachers allowed nomination forms to be promoted during class time.

The nomination process recruited 40 students; but, it was challenging and time-consuming. For example, every nominee needed to be contacted individually, adding administrative work. This work was taken on by the YHCC to recruit students who were less involved in school activities or had fewer social connections at school. Other schools starting a PMN should know that recruitment requires time, energy, and early planning. Additionally, the YHCC found it more challenging to recruit boys and young men. This could be because men report higher levels of stigma towards mental health than women (Mackenzie et al., 2019). For example, a survey by Mackenzie et al., (2019) who found that younger males reported greater stigma regarding mental health (i.e. depression) than other age groups. Therefore, future recruitment strategies should consider tailoring invites to certain populations, such as younger men.

Social and Physical Environments

The PMN created a safe social space for mentors to learn and grow. The mentors explored mental health during activities hosted by Health Promoters. One student shared that the PMN "helped [them] flourish." This supports the findings of James et al., (2014) who found that one-on-one peer mentorship programs benefit mentees and help prepare them for adulthood. The PMN also challenged students' ideas of peer support and mental health. For example, some students wanted to help others with one-on-one support. Health Promoters, the YHCC, and other school staff reinforced that the PMN was not meant to be a counselling initiative rather a mental health promotion initiative for the school population. The concepts of whole school approaches (i.e., policies, environments, engagement) may need to be revisited and re-emphasized with students and staff as there may be a tendency to focus on individual interventions and disease outcomes rather than population mental health promotion. Recruitment strategies could include emphasizing health promotion language to remind students this is a population health initiative and not a counselling initiative.

The Flourishing Event, led by students for students, was viewed as widely successful, as reported by teachers, staff, and students. Feedback from the YHCC found that the Flourishing Event created space to have fun, reduce stress, and connect with others. Increasing social connection strengthens feelings of belonging, improving overall physical and mental health (Holt-Lunstad & Steptoe, 2022). The success of the Flourishing Event showed mentors the benefits of taking a whole school approach to influence a positive mental health culture. This contrasts with the vaping education sessions, where many mentors reported disengagement from the students. Unlike the vaping session that was pre-packaged, planned, and delivered to a cohort of students, the Flourishing Event had a more meaningful youth engagement. It targeted the whole school, and everyone had a chance to participate.

Learning and Evaluation

Reflexive monitoring is an evaluation method where practitioners reflect on their practice in real-time, allowing for adjustments and responses to initiatives as they unfold (Lodder et al., 2020). A systematic review of factors influencing the implementation of whole school interventions to prevent substance use and violence by Ponsford et al., (2022) found that reflexive monitoring was crucial for assessing and adjusting the implementation of interventions within schools. The Health Promoters engaged in reflexive monitoring after each initiative, through debriefs with school staff, to improve health promotion practices and document the learning of the PMN.

Understanding setting approaches to health promotion are essential for health promotion practice. The competencies for Health Promoters are outlined in the Canadian Public Health Association’s action statement for health promotion in Canada and include action items specific to supporting settings approaches to health promotion (i.e., schools, hospitals, workplaces) (CPHA, 1996). Health promoters took on distinct roles within the school setting, and no one was "assigned" to school health promotion. This meant that the Health Promoters shared responsibilities amongst each other and built capacity within the team helping all team members become knowledgeable in school health promotion. This means that any time a school reaches out to the health promoters, any member of the team could help a school in their response.

Discussion

Planning and implementing long-term mental health promotion initiatives provide the best chance of demonstrating effectiveness over time (The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s Youth Council, 2015). However, the amount of time and resources required to evaluate creates an ongoing challenge when it comes to evaluating the effectiveness of approaches to mental health promotion in school settings. Therefore, the YHCC and school partners passed along the learnings of the PMN to the school’s grade 12 leadership class teacher and students to integrate into their local curricula. This approach provided projects for the students and gave the YHCC more time and resources to focus on other health promotion projects within the school to meet its unique needs.

Whole school approaches to peer mentorship networks can benefit more students than traditional one-on-one approaches. Health promotion champions at schools could consider initiatives that engage students of all ages like the Flourishing Event. Researchers and practitioners could consider adapting other programs to adopt whole school approaches and evaluate the implementation of these initiatives. It is important to note that while teacher’s mental health was not a focus of the PMN, this is an important area for further study.

This paper described the formation and implementation of a peer mentorship network focused on improving school mental health. Other studies have explored mental illness, but this paper offers a look into mental health outcomes. These findings are not generalizable; but, may be transferable to other high schools using a HPS framework in a post COVID-19 era.

Conclusion

This paper provides learnings and insights for the implementation of a peer mentorship network focused on improving mental health using a whole school approach. The PMN arose during a post-COVID-19 era when many students felt socially disconnected from their peers and communities. Health Promoters offered knowledge, facilitation, and education to the PMN and reinforced the purpose of the PMN which was to: focus on school mental health, instead of traditional one-on-one counselling. Peer mentors enjoyed delivering fun-focused activities for the whole school rather than vaping education sessions to classrooms. Partnerships with the YHCC and school administration were essential to the success of the PMN, which, as one student said, "helped me flourish." Further studies are required to demonstrate the impacts of whole school approaches on mental health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Health Promotion, Mental Health, and Addictions Nova Scotia Health. We would like to thank Millwood High School for their commitment to health-promoting schools.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

Caldwell, H., Hancock, F. C. L., & Kirk, S. (2021). The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health and Well-Being of Children and Youth in Nova Scotia: Youth and Parent Perspectives. Frontiers Pediatric , 17(9).

Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH). (n.d.). CATCH My Breath a nicotine vaping prevention program. Retrieved January 21, 2024, from https://letsgo.catch.org/bundles/catch-my-breath-canada

CPHA. (1996). Action statement for health promotion in Canada. https://www.cpha.ca/action-statement-health-promotion-canada

Findlay, L., & Arim, R. (2020). Canadians report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00003-eng.htm

Holt-Lunstad, J., & Steptoe, A. (2022). Social isolation: an underappreciated determinant of physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 232–237.

James, A. I., Smith, P. K., & Radford, L. (2014). Becoming grown-ups: a qualitative study of the experiences of peer mentors. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(2), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2014.893008

Karcher, M. (2009). Increases in academic connectedness and self-esteem among high school students who serve as cross-age peer mentors. Professional School Counselling, 12(4).

Keyes, C. L. M. (2022). The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 43(2), 207–222.

Kontak, J., Caldwell, H., Quann, E., Hancock Friesen, C., Machat, S., Barkhouse, K., & Kirk, S. F. L. (2023). Health promoting schools in Nova Scotia: past, present and future. Physical Activity and Health Education Journal, 88(1).

Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S., Waters, E., Komro, K., Gibbs, L., Magnus, D., & Campbell, R. (2015). The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. In BMC Public Health (Vol. 15, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y

Lodder, M., Allaert, K., Hölscher, K., Notermans, I., & Frantzeskaki, N. (2020). Reflexive monitoring: using continuous evaluation techniques to adapt your nature-based solution planning process in real-time.

Mackenzie, C. S., Visperas, A., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Oliffe, J. L., & Nurmi, M. A. (2019). Age and sex differences in self-stigma and public stigma concerning depression and suicide in men. Stigma and Health, 4(2), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000138

McIsaac, J. L. D., Read, K., Veugelers, P. J., & Kirk, S. F. L. (2017). Culture matters: A case of school health promotion in Canada. Health Promotion International, 32(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat055

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2022). Evidence reviews for whole-school approaches: Social, emotional and mental wellbeing in primary and secondary education: Evidence review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589477/

Noll, V. (1997). Cross-age mentoring program for social skills development. The School Counsellor, 44(3), 239–242.

Nova Scotia Health. (2022). Nova Scotia Health By the Numbers 2021-22. https://Www.Nshealth.ca/AnnualReport2021-22/.

Peer Support Canada. (2023). About us. https://peersupportcanada.ca/

Petosa, R. L., & Smith, L. H. (2014). Peer mentoring for health behavior change: a systematic review. American Journal of Health Education, 45(6), 351357. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2014.945670

PHAC. (2017). Measuring positive mental health in Canada: myths and facts. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/healthy-canadians/migration/publications/healthy-living-vie-saine/myths-facts-mental-health-2016-mythes-realites-sante-mentale/alt/pub-eng.pdf

Ponsford, R., Falconer, J., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Bonell, C. (2022). What factors influence implementation of whole-school interventions aiming to promote student commitment to school to prevent substance use and violence? Systematic review and synthesis of process evaluations. BMC Public Health, 22(2148).

Pulimeno, M., Piscitelli, P., Colazzo, S., Colao, A., & Miani, A. (2020). School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. In Health Promotion Perspectives (Vol. 10, Issue 4, pp. 316–334). Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2020.50

Statistics Canada. (2019). Canada’s population estimates : Age and sex, July 1, 2019. 1–6.

Statistics Canada. (2023, June 11). Perceived mental health, by age group, Table 13-10-0096-06.

The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s Youth Council. (2015). The mental health strategy for Canada: a youth perspective.

Turunen, H., Sormunen, M., Jourdan, D., Von Seelen, J., & Buijs, G. (2017). Health Promoting Schools-a complex approach and a major means to health improvement. In Health Promotion International (Vol. 32, Issue 2, pp. 177–184). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dax001

Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 17(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y

WHO & UNESCO. (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school.