Mandatory School Weight Room Hours

Abstract

Resistance training (RT) participation rates are low, particularly in teenage girls. Requiring RT in high school Physical Education (PE), may increase engagement. The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of requiring supervised RT hours on students’ RT participation. We collected logbooks documenting students’ completion of the required 55 hours of physical activity. We compared RT participation between the intervention school (IS) which required 6 hours of supervised RT, and a control school (CS) using quantile regression. Intervention school students reported more RT minutes than CS students (median 1015.0 vs. 558.8 minutes); differences were only significant for the 25th percentile (489.5 vs. 135.0 minutes; p < 0.0001). The risk of logging zero RT minutes was elevated for the CS (Relative Risk 2.6; Confidence Interval 1.13-5.95). Sex differences in RT minutes were only significant at the 75th percentile (802 minutes higher for boys; p = 0.012). Mandatory supervised RT was most effective in facilitating RT among students with the lowest participation and did not lead to equal participation between girls and boys with the highest participation minutes. Adding a minimal number of required RT hours to the high school PE curriculum may lead to additional RT participation in some students.

An unconventional classroom: the effect of mandatory supervised resistance training hours in the high school Physical Education curriculum on student participation in subsequent resistance training activities

Muscle strength peaks in the 3rd decade of life, after which a steady decline is observed. After the age of 50, the rate of strength loss is in the range of 15% per decade (Keller & Engelhardt, 2013). Maintaining muscular fitness as we age protects against frailty, and cardiovascular, metabolic, and bone disease; decreases the risk of falls; and improves quality of life (Momma et al., 2022; Shaw et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2014). Maximizing muscular fitness at a young age is imperative, as greater strength in adolescence is associated with a 20-35% lower risk of early death from any cause (Ortega et al., 2012). While it was previously believed that resistance training (RT) was ineffective in individuals lacking adult hormone levels (American Academy of Pediatrics, & Committee on Sports Medicine, 1983), we now know RT can lead to pronounced strength gains in children and youth, particularly during the peak growth phase in adolescence (Lesinski et al., 2020) Strength building activities are also a necessary component of youth sports injury prevention programs (Lauersen et al., 2014; Sugimoto et al., 2016), and they are safe and effective for this population if proper instruction and supervision are provided (Lloyd et al., 2014).

Despite large investments in public education initiatives, physical activity participation rates, in general, are low throughout the lifespan, with a marked decline among youth as they reach adolescence (Statistics Canada, 2019). Less than half of children and youth are meeting the target activity level of 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) needed daily for good health, and boys are twice as likely as girls to reach the target (Statistics Canada, 2019). In addition to MVPA, which is most often acquired through aerobic activities, children and youth are advised to undertake activities to strengthen muscle and bone at least three times per week (Canadian Society of Exercise Physiologists, 2021). However, youth participation rates in RT are even lower than those for aerobic exercise. Among adolescents, participation in RT ranges from less than 1% to 12% (Hulteen et al., 2017; Nagata et al., 2020), with only 4% of girls (compared to 29% of boys) reporting participation in ‘muscle-enhancing behaviors’ that could include lifting weights or exercise (Nagata et al., 2020).

The significantly lower RT participation rate in girls could be due in part to gendered barriers to participation, including the traditional view that training with weights and gaining muscle are masculine traits and not socially desirable for girls (Coen et al., 2018). Girls and women also report a lack of knowledge, a concern of looking weak and uncoordinated, and intimidating male-dominated exercise spaces as barriers to RT participation (Parsons & Ripat, 2020; Peters et al., 2015). However, the presence of a knowledgeable woman role model in RT environments can counteract those barriers and help facilitate participation (Author 1). Without attention to gendered barriers, the inability of at least half the population to access RT environments could have long lasting negative effects, as youth who demonstrate low strength levels seem to maintain that poor muscular fitness into adulthood (Fraser et al., 2017), with the associated implications for poor health and mobility and premature mortality (Momma et al., 2022; Shaw et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2014).

According to the World Health Organization (2021), interventions delivered through school environments can be some of the most important for improving health, as well as influencing societal factors (e.g., gender equity) that contribute to a healthy population. Previous school-based programs that aimed to increase physical activity participation (including RT) amongst girls have had some success (Dewar et al., 2014; Lubans et al., 2012; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2003); however, study activities were voluntary and not embedded as a required component within the schools’ existing programs. We know that program success requires more than providing opportunities for participation – strong policies that steer behavior in a desired direction are necessary (Gielen & Green, 2015).

Given that building high levels of strength early in life is advantageous for the prevention of a wide range of health conditions, and at least half the population encounters gender-related barriers to undertaking appropriate activities to build muscular fitness, we require better understanding of the impact of inclusive school-based RT initiatives targeted at youth. The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of a school’s policy to include RT hours in the Grade 11 & 12 physical education (PE) curriculum, supervised by a woman Kinesiologist, on students’ additional participation (beyond the mandatory 6 hours) in RT activities. The specific objectives were to 1) determine the proportion of girls and boys in Grades 11 & 12 who exceed the intervention school’s required 6 RT hours; 2) compare the number of RT participation hours reported as part of the Grade 11 & 12 PE curriculum between girls and boys at the intervention and control schools; and 3) explore how self-reported weight room use aligns with objectively observed use.

Methods

Experimental Approach to the Problem

We used a natural experiment, exploratory design to determine whether including RT hours supervised by a woman Kinesiologist in the Grade 11 & 12 PE curriculum results in more participation in RT activities compared to students attending a school that does not require mandatory supervised RT hours. The intervention school requires students to complete 6 hours in the school weight room as part of the 55 physical activity hours needed to receive their Grade 11 & 12 PE credits. The control school is of a similar size (approximately 1300 students) to the intervention school but does not have mandatory supervised weight room hours as part of their required 55 hours of physical activity in Grade 11 & 12 PE.

Participants

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the first author’s institution (University of Manitoba) and the appropriate school divisions. Students in Grades 11 & 12 who were enrolled in PE class during the fall 2019 and winter 2023 terms were invited to participate in this study. Two hundred and twenty-five students, 134 from the control school (72 girls) and 91 from the intervention school (57 girls), volunteered for the study. Information describing the risks and benefits of the study and consent forms were sent home with students in their welcome package at the beginning of the school term. No students were excluded, as PE is mandatory for every Grade 11 & 12 student in our province. We intended to complete the study in one school year (2019/2020); however, the participating schools were completely shut down and/or operated in a hybrid capacity due to the Covid-19 pandemic from March 2020-June 2022. We resumed the study as soon as possible after PE reverted to pre-pandemic delivery methods and we completed data collection in June 2023.

Procedures

At the start of the school term, a Research Assistant (RA) attended each Grade 11 & 12 PE class at both schools. The RA gave a short explanation of the study and answered students’ questions. Consent forms were sent home to be read and signed by parents/guardians and then returned to the PE teacher. As part of their PE class at both schools, each Grade 11 & 12 student must log a minimum of 55 hours of physical activity during the term (see Appendix A) including the type of activity undertaken, and the duration and location of the activity. To ensure more accurate and consistent data reporting we provided PE teachers and students with instructions on how to report RT activities in their physical activity logs. We asked students to use terms such as “resistance training”, “weight training”, and “exercises with bodyweight” to attempt to distinguish from other types of activities. We added “sex assigned at birth” to the logs in order to compare RT participation between girls and boys, as girls are known to participate in physical activity, including RT, at lower rates compared to boys (Nagata et al., 2020; Statistics Canada, 2019). The volume of physical activity reported in the log at the end of the term must total at least 55 hours to receive their PE credit. For the intervention school students, 6 of the 55 hours must be completed in the school weight room, under the supervision of the school’s Kinesiologist. Those 6 hours are logged on a separate form and submitted to the PE teacher. After the school term was over and the PE teachers had assigned student grades and confirmed they no longer required the physical activity logs, the RA went to each school and collected the logs and the completed consent forms from the PE teachers. We did not collect the forms confirming completion of the 6 hours in the weight room at the intervention school as these were required to receive course credit and did not provide us with pertinent information. Physical activity logs relating to any students for whom we did not have a signed consent form were immediately deleted (electronic form) or destroyed (paper form). Once we created a master list of all remaining participants, the logs were de-identified by replacing the student’s name with their study ID, and obscuring any other potentially identifying information (e.g., parent’s signature).

From the information in the physical activity logs, an RA entered each student’s grade, sex assigned at birth, and the number of minutes, the location, and date they reported participating in any type of RT activity during the school term into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, 2018. Microsoft Excel, available at: https://office.microsoft.com/excel). As varying terminology arose in the logs that perhaps could be interpreted as RT, the RA discussed with the research team which terms and activities were appropriate for inclusion. For the purposes of this study, we were interested in organized, structured RT activities that involved either body weight or external resistance. Although there are many physical activities and sports that can increase muscle mass and strength (e.g., gymnastics), the intervention being assessed (mandatory weight room hours supervised by a Kinesiologist) was meant to educate students on the appropriate and effective use of RT equipment and exercises specifically. Therefore, we excluded activities such as skipping rope, jumping jacks, and Pilates, but included terms such as “core exercises”, “push-ups”, and “arm workout”.

In preparing for this study, anecdotal information from the PE teachers suggested that PE students may fabricate some of the physical activity hours recorded in their logs. We also know that self-report can significantly overestimate an individual’s physical activity level (Dyrstad et al., 2014). Therefore, to explore the accuracy of self-reported weight room use, an RA observed the intervention school weight room for the entire school day for three, two-week blocks of time during the fall 2019 term. Three different time periods were chosen to capture any variety in weight room activity throughout the term. The RA kept a written log of the names of all Grade 11 and 12 students who engaged in a workout in the weight room during those 6 weeks, with the students signing in and out to indicate the approximate duration of their workout. The RA was assisted in identification of Grade 11 and 12 students by the school Kinesiologist when needed. At the end of the school term, the list of weight room users was compared against the signed consent forms we received, and the name of any student who had not provided a signed consent form to participate in the study was obscured and their weight room attendance was not included in the study.

Intervention

Day-to-day delivery of the PE curriculum continued as planned by the PE teachers in both schools with no interference from the research team for the duration of the 5-month school term. Grade 11 & 12 PE consisted of classroom-based lectures and activities regarding general health topics, and the completion of the physical activity log with each student independently acquiring a minimum of 55 hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during the school term. There was no provision of in-school physical activity during their scheduled PE class. The 6 hours of mandatory weight room use by students in the intervention school could occur at a time of the student’s choosing as long as the Kinesiologist was present and signed off on the hours. The Kinesiologist provided each student with a general introduction to the weight room during their first visit and was available to suggest exercises and activities and answer questions during any subsequent visit. Students at the intervention school could use the weight room during lunch hour, during a spare, and before/after school on some weekdays when the Kinesiologist was in attendance. Students at the control school could use the weight room when a staff member was available and willing to supervise, which was most often at noon hour.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated means, standard deviations, medians, and ranges as appropriate for the data. Resistance training data in our sample were found to be heavily skewed and zero-inflated, which is not uncommon for measures with lower bounds. This combination renders the distributional assumptions of conventional statistical methods like linear regression untenable. Therefore, we used quantile regression, which makes no such assumptions and can model any chosen quantile as a function of the predictors. This allows predictors to have a different magnitude of effect at different quantiles, offering a potentially richer exploration of relationships. We focused on the first quartile (25th percentile), median, and third quartile (75th percentile) as our thresholds of interest for testing the effects of sex, intervention, and their potential interaction, using multivariable models. When the sex-intervention interaction was not significant, we reported the results from a model with only the main effects. Additionally, to examine whether mandatory supervised RT hours in PE significantly reduced the risk of non-participation in RT we compared the frequency of any non-zero RT minutes (participation) between schools. Analyses were performed with R version 4.3.1. We used the “quantreg” package to fit the quantile regression models (Koenker, 2021). Confidence intervals were generated via bootstrapping with 10,000 replications.

We used descriptive statistics to explore the accuracy of student self-report of RT. We compared the number of self-reported RT minutes in the PA log entries of each student that corresponded with each observed visit to the school weight room as recorded on the sign in/out log supervised by the RA. We tallied the number of weight room visits that aligned in the PA logs and the sign in/out log and checked the accuracy of the duration of each observed weight room visit.

Results

Of the 91 participants from the intervention school, 6 (6.6%) reported no RT in their physical activity log, indicating they did not participate in additional RT beyond the required 6 hours (4 girls, 2 boys). In the control school, 23 of 134 (17.2%) reported no additional RT hours.

Students at the intervention school reported more RT minutes than students at the control school (Table 1). The risk of being a non-participant (i.e., logging zero RT minutes) was more than twice as high for the control school compared to the intervention school [Relative Risk (RR) = 2.6; Confidence Interval (CI) 1.13-5.95]. The effect of the intervention (i.e., Kinesiologist-supervised required weight room hours) was statistically significant for the 25th percentile only, with borderline significance at the 50th and 75th percentiles (Table 2). Students in the 25th percentile at the intervention school reported 455 more RT minutes on average than students in the 25th percentile at the control school.

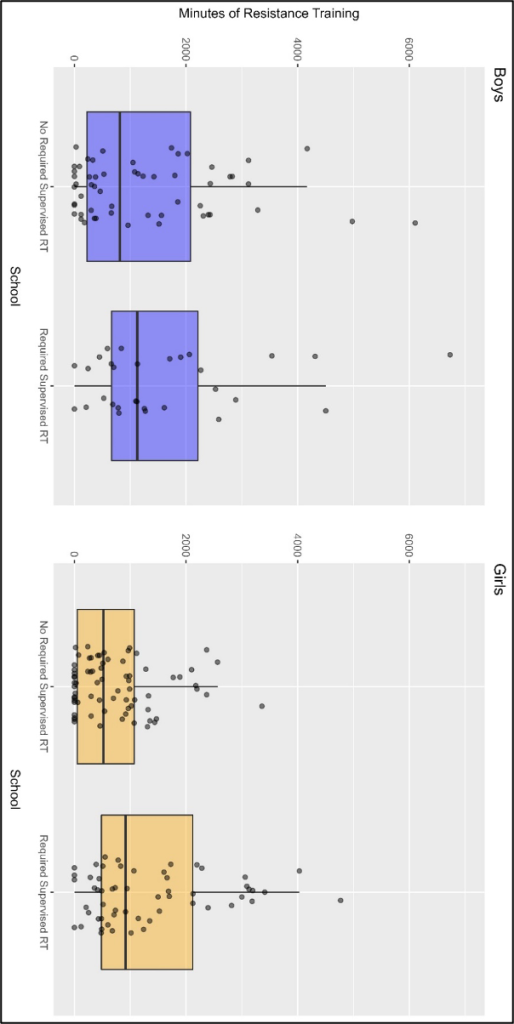

The proportion of girls reporting RT in their PA log from the intervention school was greater than that of the control school (intervention school, 64%; control school, 56%). There was no significant interaction between intervention and sex at any of the three modeled percentiles. However, there is some indication that the intervention effect at the 75th percentile may be larger for female students than male students (see Figure 1). The increase in 75th percentile RT time for boys receiving intervention is 131 minutes, whereas for girls it is 1049 minutes (interaction p = 0.14). Overall, marginal sex differences in RT minutes were only statistically significant at the 75th percentile (p = 0.012) (Table 2), for which boys’ reported RT time was 802 minutes higher than that reported by girls. In other words, girls and boys are statistically similar in their resistance training minutes until the more extreme upper values are reached.

During the 6 weeks of direct weight room observation at the intervention school, there were 324 discrete visits by 71 individual study participants. One hundred seventy-four (54%) of the discrete student weight room visits were within a reasonable timeframe (2 days) of a date listed in their PA log. Of those 174 visits, 25 underreported the exercise duration in the students’ PA logbook compared to the time spent in the weight room recorded in the RA-supervised sign in/out sheet (underreported range: 5-45 minutes; median: 15 minutes); 55 reported the same number of minutes as the sign in/out sheet; and 94 overreported the exercise duration in the students’ PA logbook (overreported range: 5-45 minutes; median: 10 minutes). The remaining weight room visits recorded in the RA-supervised sign in/out sheet either did not match reasonably well (within 2 days) to a corresponding date in the student’s PA logbook, or the dates in the PA log were completely missing, or the reported location of RT participation on the date was not the school weight room.

Discussion

Introducing Grade 11 and 12 students to supervised resistance training as a required part of the physical education curriculum resulted in some students pursuing additional RT activities more often compared to students who had access to a school weight room but not in a mandatory, supervised manner. The median number of RT minutes reported by the intervention school was almost twice as large as that of the control school. Only 6.5% of the intervention school students reported no RT minutes (above and beyond their mandatory 6 hours), compared to 17% of the control school students who reported no RT minutes in their PA logs. The effect of the intervention was strongest for students in the 25th percentile, indicating that the intervention was most effective at “raising the bottom up”, allowing more students to get at least some RT minutes, however minimal. This is consistent with the strongly reduced risk of being a non-participant (i.e., recording zero RT minutes) in the intervention school.

Our results are consistent with previous work that showed supervised school-based RT programs induce greater positive changes compared to unsupervised programs in improving fitness and performance levels (Cohen et al., 2021). Our study adds to that literature by demonstrating that supervised programs can positively affect participation as well. Being able to positively influence RT participation among all students, especially those who participate less frequently, is immensely beneficial for improving muscular fitness at a younger age. There is growing awareness of the importance of building up a reservoir of muscular fitness early as well as maintaining it through the lifespan (Steele et al., 2017), as low strength levels have been linked to the development of osteoarthritis (Øiestad et al., 2015), a higher risk of cardiovascular, metabolic, and bone disease (Smith et al., 2014), and may be a risk factor for sports injuries (Shultz et al., 2012). Requiring RT participation in PE class during late adolescence also teaches the students an accessible physical activity that they can continue to participate in as they become adults and leave high school. Adults are much more likely to engage in structured exercise such as resistance training compared to participating in organized sports, which are often the focus of typical PE classes (Ham et al., 2009). Participation in RT as little as once per week has been shown to increase strength in youth (Behm et al., 2023), demonstrating that any participation is better than none for both their immediate health and their longer-term wellbeing.

Boys reported more RT participation than girls, but only the highest level of participation (75th percentile) demonstrated statistical significance, where boys reported 802 more minutes of RT than girls. The difference in RT participation between girls and boys did not depend on the school. Based on previous work showing that girls do not participate in physical activity or RT as much as boys (Nagata et al., 2020; Statistics Canada, 2019), we anticipated similar findings in our study. However, we also anticipated that our intervention, specifically targeted to reduce gendered barriers to RT participation (i.e., supervision of RT hours in the school weight room by a woman Kinesiologist), would lead to increased participation among the girls at the intervention school compared to the control school. This did not occur. Typically, large sample sizes are required to detect interactions, which may have affected our ability to detect a statistically significant difference in RT minutes between girls at the intervention school and girls at the control school. There appears to be a trend towards a difference, as resistance training totals for the girls at the intervention school appear higher than for those at the control school (see Table 1); a larger sample size may have allowed us to detect a difference. In addition, participation in this research study was voluntary, which may have resulted in girls who were more interested in the topic of RT and already participating in RT activities volunteering in higher numbers. This may have masked a difference in RT participation between schools and affected our results. It would be worth repeating the study with data from all Grade 11 & 12 students to address this limitation.

Previous research has shown that there are highly gendered pressures and expectations of behaviors associated with the weight room that affect participation for both women and men (Coen et al., 2018; Dworkin, 2001; Dwyer et al., 2006; Peters et al., 2015). Girls generally do not see the weight room as a place where they belong, and they report that a knowledgeable woman role model in the space can be a key motivator to their participation (Author 1). Having required RT hours in high school PE supervised by a woman Kinesiologist addresses these barriers. They act as role models to show girls (and others) that they can indeed be in the weight room and that anyone can participate in RT; it is not reserved solely for the most masculine of boys and men. Girls in our study reported significantly lower RT hours than boys only at the very highest level of participation (75th percentile). This perhaps suggests that gendered barriers are weakening, gaining muscularity is not feared by girls as much as in the past (Bozsik et al., 2018), and strength training is becoming more ‘mainstream’ as evident from the billions of views of the social media hashtag “#girlswholift” (Norris, 2023). However, the trend we can see in the lower RT minutes for girls across the quantiles suggests there is still room for improvement in facilitating and encouraging girls’ participation in RT.

The accuracy of the students’ self-report aligned with previous research (Dyrstad et al., 2014), in that 54% of the time, students overreported the duration of their RT workout. However, 32% of the visits were logged accurately, and 14% of the school weight room visits were underreported in terms of their duration, indicating that students do not uniformly intend to misrepresent their activities in their favor. An overrepresentation of 10 minutes for one or two RT sessions is likely of limited practical importance to either the student or the PE teacher. However, if a student is consistently overreporting their RT sessions by 10 minutes and logging 50 or more RT sessions (as some students in our study did) in a 5 month period, this is important for PE teachers to be aware of. Some of the mismatches between PA log entries and the RA-supervised sign in/out sheet could also have reflected students who had already completed their required 55 hours of physical activity for the term and stopped recording in their PA log.

The strength of our study is the natural experiment approach; the intervention we describe had already been in place for a number of years, it was functioning well, and was strongly supported by students and staff at the school. We did not require changes to the PE curriculum, and the only additional time required of school staff was the collection of consent forms and providing the PA logs to the RA at the end of term. This study is the first, as far as we are aware, to investigate the effect of a school-based RT program on additional, independent RT participation. Many studies have investigated and found health and performance benefits of school-based programs that included an RT component (Bayne-Smith et al., 2004; Kennedy et al., 2018; Lubans et al., 2010; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2010). However, the wide range of health benefits to be gained from RT for youth are already well established (Chaabene et al., 2020). Participation is the key – without participation, there are no health benefits. The embedding of a Kinesiologist in the school weight room to supervise required RT hours within the PE curriculum led many students to pursue additional RT hours beyond their course requirements. The integration of a Kinesiologist in the manner described in this study is much less demanding and complex than introducing new, intricate programs that require extensive training of and significant time commitments from existing school staff, and that are likely to fade from use when the researchers leave (Friend et al., 2014). It also aligns with recent calls to incorporate RT into existing school systems and processes by employing educated, experienced strength and conditioning specialists (Till et al., 2021). The hiring of a Kinesiologist to staff a school weight room and supervise mandatory RT hours for PE classes can be a challenge due to the additional funds needed from a school’s budget. However, because it does not require any additional time commitment from existing PE staff, and the Kinesiologist and their role fits easily into existing physical spaces and schedules, a school based exercise program such as the one at the intervention school is more likely to continue and be successful if a dedicated staff member such as a Kinesiologist is hired (Friend et al., 2014).

There are some limitations to consider with our study. We relied on the PA logs for data, many of which were paper logs filled out with pen/pencil by the student, and as a result we were occasionally unable to read the student’s writing and so we may have missed some occurrences of RT. Sometimes the terms used by the students did not make it entirely clear whether that activity could be counted as RT. When in doubt, we did not include the term or the minutes associated with that activity. We kept a record of included and excluded terms to ensure consistency. We did not collect data on factors such as students’ sport participation, socioeconomic status, or health status which may have acted as confounders and influenced the results. Feasibility restraints allowed us to simply compare voluntary participants from two similar schools in terms of their size and the demographics of the area of the city in which they were located. We did not compare the intervention school employing the woman Kinesiologist to a school that had a weight room with a man supervising, as we are not aware of any such situation in our city. However, our previous work suggests that having a woman role model present is integral to engaging high school girls in RT (Author 1). Future research could compare a woman supervisor with a man supervisor in high school weight rooms to determine the effect on overall participation in RT activities, and whether there are different outcomes for girls and boys.

Translation to Health Education Practice

We recommend the following for health educators:

- Build in a minimal number of required RT hours into the PE curriculum to introduce the activity to all students. In our study, 6 required hours were enough to encourage continued participation among many students.

- Provide knowledgeable, experienced women role models in the school RT environment to provide instruction, and facilitate a safe, welcoming atmosphere for everyone.

- Lobby for the hiring of a designated exercise professional to supervise the required RT hours to decrease additional load on teachers and increase the chances that the program will be a success.

- Gather ongoing feedback from students regarding the barriers and facilitators to participating in RT, especially from girls, to continuously improve the program and decrease gendered-related obstacles to participation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Manitoba Medical Service Foundation under Grant #8-2019-09. The authors thank Kayla Duna, and the PE teachers at Grant Park High School and Garden City Collegiate for their assistance with the study.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Reference

American Academy of Pediatrics, & Committee on Sports Medicine. (1983). Weight training and weight lifting: Information for the pediatrician. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 11(3), 157-161. doi:10.1080/00913847.1983.11708490

Bayne-Smith, M., Fardy, P. S., Azzollini, A., Magel, J., Schmitz, K. H., & Agin, D. (2004). Improvements in heart health behaviors and reduction in coronary artery disease risk factors in urban teenaged girls through a school-based intervention: The PATH program. American Journal of Public Health, 94(9), 1538-1543. doi:94/9/1538

Behm, D. G., Granacher, U., Warneke, K., Aragão-Santos, J. C., Da Silva-Grigoletto, M. E., & Konrad, A. (2023). Minimalist training: Is lower dosage or intensity resistance training effective to improve physical fitness? A narrative review. Sports Medicine, 54, 289-302. doi:10.1007/s40279-023-01949-3

Bozsik, F., Whisenhunt, B. L., Hudson, D. L., Bennett, B., & Lundgren, J. D. (2018). Thin is in? Think again: The rising importance of muscularity in the thin ideal female body. Sex Roles, 79(9), 609-615. doi:10.1007/s11199-017-0886-0

Canadian Society of Exercise Physiologists. Canadian 24-Hour movement guidelines for children and youth 2021. Retrieved from: https://csepguidelines.ca/

Chaabene, H., Lesinski, M., Behm, D. G., & Granacher, U. (2020). Performance-and health-related benefits of youth resistance training. Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 36(3), 231-240.

Coen, S. E., Rosenberg, M. W., & Davidson, J. (2018). “It's gym, like g-y-m not J-i-m”: Exploring the role of place in the gendering of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine, 196, 29-36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.036

Cohen, D. D., Carreño, J., Camacho, P. A., Otero, J., Martinez, D., Lopez-Lopez, J., . . . Lopez-Jaramillo, P. (2021). Fitness changes in adolescent girls following in-school combined aerobic and resistance exercise: Interaction with birthweight. Pediatric Exercise Science, 34(2), 76-83.

Dewar, D. L., Morgan, P. J., Plotnikoff, R. C., Okely, A. D., Batterham, M., & Lubans, D. R. (2014). Exploring changes in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and hypothesized mediators in the NEAT girls group randomized controlled trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(1), 39-46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.02.003

Dworkin, S. L. (2001). "Holding back": Negotiating a glass ceiling on women's muscular strength. Sociological Perspectives, 44(3), 333-350. doi:10.1525/sop.2001.44.3.333

Dwyer, J. J. M., Allison, K. R., Goldenberg, E. R., Fein, A. J., Yoshida, K. K., & Boutilier, M. A. (2006). Adolescent girls' perceived barriers to participation in physical activity. Adolescence, 41(161), 75.

Dyrstad, S. M., Hansen, B. H., Holme, I. M., & Anderssen, S. A. (2014). Comparison of self-reported versus accelerometer-measured physical activity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(1), 99-106. doi: 110.1249/MSS.1240b1013e3182a0595f.

Fraser, B. J., Schmidt, M. D., Huynh, Q. L., Dwyer, T., Venn, A. J., & Magnussen, C. G. (2017). Tracking of muscular strength and power from youth to young adulthood: Longitudinal findings from the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport, 20(10), 927-931. doi: 910.1016/j.jsams.2017.1003.1021.

Friend, S., Flattum, C. F., Simpson, D., Nederhoff, D. M., & Neumark‐Sztainer, D. (2014). The researchers have left the building: What contributes to sustaining school‐based interventions following the conclusion of formal research support? Journal of School Health, 84(5), 326-333.

Gielen, A. C., & Green, L. W. (2015). The impact of policy, environmental, and educational interventions. Health Education & Behavior, 42(1_suppl), 20S-34S. doi:10.1177/1090198115570049

Ham, S. A., Kruger, J., & Tudor-Locke, C. (2009). Participation by US adults in sports, exercise, and recreational physical activities. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 6(1), 6-14. doi:10.1123/jpah.6.1.6

Hulteen, R. M., Smith, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Barnett, L. M., Hallal, P. C., Colyvas, K., & Lubans, D. R. (2017). Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine, 95, 14-25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.027

Keller, K., & Engelhardt, M. (2013). Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles, Ligaments, and Tendons Journal, 3(4), 346-350.

Kennedy, S. G., Smith, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Peralta, L. R., Hilland, T. A., Eather, N., . . . Salmon, J. (2018). Implementing resistance training in secondary schools: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50(1), 62-72.

Koenker, R. (2021). quantreg: Quantile Regression. R package version 5.85. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=quantreg

Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871-877. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092538

Lesinski, M., Herz, M., Schmelcher, A., & Granacher, U. (2020). Effects of resistance training on physical fitness in healthy children and adolescents: An umbrella review. Sports Medicine, 50(11), 1901-1928. doi:10.1007/s40279-020-01327-3

Lloyd, R. S., Faigenbaum, A. D., Stone, M. H., Oliver, J. L., Jeffreys, I., Moody, J. A., . . . Myer, G. D. (2014). Position statement on youth resistance training: The 2014 International Consensus. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(7), 498-505. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092952

Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J., Dewar, D., Collins, C. E., Plotnikoff, R. C., Okely, A. D., . . . Callister, R. (2010). The Nutrition and Enjoyable Activity for Teen Girls (NEAT girls) randomized controlled trial for adolescent girls from disadvantaged secondary schools: Rationale, study protocol, and baseline results. BMC Public Health, 10, 652-2458-2410-2652. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-652

Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J., Okely, A. D., & et al. (2012). Preventing obesity among adolescent girls: One-year outcomes of the nutrition and enjoyable activity for teen girls (NEAT girls) cluster randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(9), 821-827. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.41

Momma, H., Kawakami, R., Honda, T., & Sawada, S. S. (2022). Muscle-strengthening activities are associated with lower risk and mortality in major non-communicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(13), 755-763.

Nagata, J. M., Ganson, K. T., Griffiths, S., Mitchison, D., Garber, A. K., Vittinghoff, E., . . . Murray, S. B. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of muscle-enhancing behaviors among adolescents and young adults in the United States. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 34(2), 119-129.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Hannan, P. J., & Rex, J. (2003). New Moves: A school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine, 37(1), 41-51. doi:S0091743503000574

Neumark-Sztainer, D. R., Friend, S. E., Flattum, C. F., Hannan, P. J., Story, M. T., Bauer, K. W., . . . Petrich, C. A. (2010). New Moves—preventing weight-related problems in adolescent girls: A group-randomized study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(5), 421-432.

Norris, R. (April 16, 2023). More women are finding their power in the weight room—And enjoying the bone-building, mood-boosting perks. Retrieved from https://www.wellandgood.com/weightlifting-women/

Øiestad, B. E., Juhl, C. B., Eitzen, I., & Thorlund, J. B. (2015). Knee extensor muscle weakness is a risk factor for development of knee osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 23(2), 171-177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.10.008

Ortega, F. B., Silventoinen, K., Tynelius, P., & Rasmussen, F. (2012). Muscular strength in male adolescents and premature death: Cohort study of one million participants. BMJ, 345, e7279. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7279

Parsons, J., Ripat, J. (2020). Understanding the experiences of girls using a high school weight room. Physical and Health Education Journal, 86(2).

Peters, N., Schlaff, R., & Knous, J. (2015). Barriers to resistance training among college-aged women. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47(5S), 733.

Shaw, S. C., Dennison, E. M., & Cooper, C. (2017). Epidemiology of sarcopenia: Determinants throughout the lifecourse. Calcified Tissue International, 101(3), 229-247. doi: 210.1007/s00223-00017-00277-00220.

Shultz, S. J., Pye, M. L., Montgomery, M. M., & Schmitz, R. J. (2012). Associations between lower extremity muscle mass and multiplanar knee laxity and stiffness. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(12), 2836-2844. doi:10.1177/0363546512461744

Smith, J. J., Eather, N., Morgan, P. J., Plotnikoff, R. C., Faigenbaum, A. D., & Lubans, D. R. (2014). The health benefits of muscular fitness for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 44(9), 1209-1223. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0196-4

Statistics Canada. Physical activity and screen time among Canadian children and youth, 2016 and 2017. (2019). Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2019001/article/00003-eng.htm

Steele, J., Fisher, J., Skivington, M., Dunn, C., Arnold, J., Tew, G., . . . Winett, R. (2017). A higher effort-based paradigm in physical activity and exercise for public health: Making the case for a greater emphasis on resistance training. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 300. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4209-8

Sugimoto, D., Myer, G. D., Barber Foss, K. D., Pepin, M. J., Micheli, L. J., & Hewett, T. E. (2016). Critical components of neuromuscular training to reduce ACL injury risk in female athletes: Meta-regression analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. doi:bjsports-2015-095596

Till, K., Bruce, A., Green, T., Morris, S. J., Boret, S., & Bishop, C. J. (2021). Strength and conditioning in schools: A strategy to optimise health, fitness and physical activity in youths. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(9),479-480.

World Health Organization (2021). WHO guideline on school health services. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029392

Table 1. Resistance training minutes for female and male students at the control and intervention schools.

|

School |

Minimum |

25th Percentile |

Median |

75th Percentile |

Maximum |

Standard Deviation |

|

Control (n=128) |

0 |

135.0 |

558.8 |

1346.5 |

6105.0 |

1074.2 |

|

Female Students (n=72) |

0 |

52.5 |

521.3 |

1073.1 |

3360.0 |

756.3 |

|

Male Students (n=56) |

0 |

225.0 |

815.0 |

2082.5 |

6105.0 |

1363.5 |

|

Intervention (n=87) |

0 |

489.5 |

1015.0 |

2100.7 |

6730.0 |

1278.4 |

|

Female Students (n=57) |

0 |

485.0 |

917.0 |

2122.5 |

4770.0 |

1150.1 |

|

Male Students (n=30) |

0 |

667.0 |

1126.0 |

2213.8 |

6730.0 |

1529.2 |

Table 2. Quantile regression model results.

|

|

Predictor |

Coefficient |

P-value |

95% Confidence Interval |

|

25th Percentile |

Intercept |

30.0 |

0.758 |

-160.12, 220 |

|

Intervention vs Control |

455.0 |

< 0.001 |

255.08, 654.92 |

|

|

Male vs Female |

175.0 |

0.097 |

-30.8, 380.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50th Percentile |

Intercept |

532.5 |

< 0.001 |

240.46, 824.54 |

|

Intervention vs Control |

384.5 |

0.085 |

-51.69, 819.69 |

|

|

Male vs Female |

204.0 |

0.422 |

-293.92, 701.92 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

75th Percentile |

Intercept |

1115.0 |

< 0.001 |

808.54, 1421.46 |

|

Intervention vs Control |

612.0 |

0.060 |

-22.43, 1246.43 |

|

|

Male vs Female |

802.0 |

0.012 |

182.27, 1421.73 |

*Coefficients estimated from a multivariable quantile regression model at three percentiles. Confidence intervals are based on bootstrapped standard errors with 10,000 replications.

Figure 1. Comparison of girls’ and boys’ resistance training minutes at the control and intervention schools.

Appendix A: Physical Activity Log

Grade ______

Sex at birth (circle one)

Female Male Other

Physical Education – Grade 11/12 Curriculum

Log Sheet for: __________________ PE Advisor: _______________________

|

Date |

Activity |

Duration |

Location |

Signature |

Grand Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|