Incorporating Water Safety Activities and Content in Physical and Health Education

Abstract

Participation in aquatic activities offers many benefits for children and youth (i.e., improved cardiovascular health, decreased obesity, increased social opportunities); however, drowning is a leading cause of unintentional death for children and youth worldwide. With the proper skills and knowledge, children and youth can enjoy safe participation in a wide-range of water-based activities. The school environment is an ideal venue to teach water-safety skills and knowledge, although barriers to this content delivery exist. Two commonly cited barriers are a lack of teacher water safety knowledge and access to aquatic facilities. This paper offers water-safety background knowledge for teachers, and includes three dry-land activities and resource links for K-12 PHE classes.

Introduction

Participation in aquatic activities offers many benefits for children and youth (i.e., improved cardiovascular health, decreased obesity, increased social opportunities) (Moffatt, 2017; Stubbs & Cumming, 2017); however, drowning is a leading cause of unintentional death for children and youth worldwide (World Health Organization, 2021). With the proper skills and knowledge, children and youth can enjoy safe participation in a wide-range of water-based activities. One of the goals of Physical and Health Education (PHE) in Canada is to equip students with the skills and knowledge so they can be active for life in a range of activities and environments (e.g., British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2016; Government of Northwest Territories, 2000; Government of Ontario, 2019; Physical and Health Education Canada, 2024). Our aim for this paper is two-fold: 1) respond to the World Health Organization’s and United Nations’ calls to action to reduce drowning incidence for children and youth through collaboration with public education, and 2) equip teachers with practical water safety knowledge and activities to deliver dry-land lessons in PHE.

The Benefits of Movement in and Around Blue Spaces

Blue spaces include all forms of naturally occurring surface water and associated infrastructure (Grellier et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2021), including lakes, rivers, oceans, canals, and harbours. These blue spaces are commonly used to facilitate tourism (i.e., cruising, whale watching), transportation, commerce, power generation, and a wide range of leisure activities (i.e., swimming, fishing, water sports) (Grellier et al., 2017; Vitale et al., 2022). In addition to natural blue spaces, there are also human-built aquatic environments (i.e., swimming pools, splash pads, water parks). Activities in these environments are often part of children’s aquatic recreation patterns in Canada (e.g., swimming lessons) (Canadian Red Cross, 2023c; Lifesaving Society, 2023).

One of the primary goals of PHE is to create “lifelong physical health and mental well-being” for students (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2016). Access to, and participation in and around blue spaces, has health and wellness benefits including decreased obesity (Smith et al., 2021), decreased depressive symptoms (Smith et al., 2021), increased opportunities for physical activity (Georgiou et al., 2021), and overall improved mental health and well-being (Georgiou et al., 2021; Vitale et al., 2022). Researchers recently explored the connection between childhood exposure to blue spaces and subjective well-being in adults in 18 countries, including Canada, and concluded that “greater exposure to blue spaces during childhood predicted better subjective well-being in adulthood” (Vitale et al., 2022, pp. 7-8). Further, these childhood experiences in blue spaces also contributed to increased intrinsic motivation to visit blue spaces in adulthood, and subsequently, more frequent visits to blue spaces (Vitale et al., 2022). Given the goals of PHE, increasing safe exposure to blue spaces aligns with the development of health and well-being in adulthood. However, participation in recreation and leisure activities in blue spaces is not without risk. Risks associated with blue spaces include, but are not limited to, contracting infectious diseases, exposure to unhealthy bacteria (i.e., blue-green algae blooms), and drowning (World Health Organization, 2014).

Drowning Prevention

Drowning is one of the leading causes of unintentional death for children and youth aged 1-14 globally, with the highest percentage of drownings occurring for those aged 1-4, followed by those aged 5-9 years (World Health Organization, 2021). In Canada, there are approximately 460 unintentional fatal drownings per year (Drowning Prevention Research Centre, 2022). Children who live near open water sources are particularly at risk (World Health Organization, 2021) and with approximately 50% of people living within 3 kilometres of an open water source (Depledge, 2021), it is essential that young people adopt water safe attitudes and behaviours, water competence (e.g., swimming), and survival skills. However, even in countries with large coastlines such as Canada, many drownings still happen inland in areas such as bathtubs, ponds, or pools, especially for young children (World Health Organization, 2014).

Swimming and water safety programs are an effective and feasible intervention for drowning prevention (World Health Organization, 2014). Given the high percentage of young children (aged 1-9) who drown (World Health Organization, 2021), it is paramount that elementary school-aged children, in particular, receive water safety education. Recently in Canada, however, a shortage of lifeguard and swim instructors has meant limited availability for learn-to-swim program offerings in many communities, and a reduction in lifeguards at outdoor venues such as lakes and beaches (i.e., Giles et al., 2023; Shingler, 2022). One suggestion to alleviate the stress of staffing shortages and lack of instructors is to use multisector collaboration to ensure children and youth receive necessary swimming and water safety education. Recent calls to action from the World Health Organization (2014, 2017) and the United Nations (2021) recommend collaboration with academic institutions, governments, and education sectors to reduce drowning. Further, in the most recent Canadian Drowning Prevention Plan (2022), the Canadian Drowning Prevention Coalition suggests embedding basic swimming and water safety skills into the public education system as one of their five overarching recommendations for drowning prevention.

Water Safety in Schools

Of the many risk factors associated with drowning, one of the most prominent is low socioeconomic status (World Health Organization, 2021). A school environment is an ideal place to introduce children and youth to water safety content, particularly due to the inclusive nature of education and the availability of education for those from all socioeconomic statuses (Ewing, 2010). Specifically, PHE is an ideal setting for water safety activities and content. PHE is compulsory for K-9 or K-10 students in Canada (depending on province/territory), and is an essential part of secondary curriculum; it empowers the whole child to access, analyze, plan, value, and make decisions for engagement in a variety of movement opportunities, including water-based activities, as well as promote health-enhancing behaviours for life (Bryan & Sims, 2020).

Recently, PHE Canada, the national organization for PHE, released the Canadian PHE Competencies, a document directed to those who develop PHE curricula across the provinces and territories of Canada. This set of competencies is meant to “set the bar high”, hold the “education community, accountable to quality [PHE]”, and encourage “all educators and school system leaders across Canada to push beyond what has been the norm [in PHE] for those who are the future” (Davis et al., 2023, p. 6). These new curriculum suggestions explicitly state the need for water safety activities and content in PHE as stated in a Grade One exemplar: “Activate safety skills and knowledge (i.e., …water safety)” (Davis et al., 2023, p. 33). This focus on safety in order to engage in a variety of movement forms continues throughout students’ education to Grade 12 learning outcomes: I.e., “Develop a risk management plan considering the risks associated with various movement opportunities” (Davis et al., 2023, p. 89).

Despite this recent shift to a more wholistic PHE curriculum that focuses on overall health and well-being, there is currently limited incorporation of water safety content in K-12 curriculum in Canada. A recent review paper (Field et al., 2022) indicates there are several barriers and challenges to incorporating swimming and water safety content into PHE. Some of the most commonly cited barriers are lack of access to aquatic facilities, scheduling challenges, and lack of teacher knowledge, confidence, and competence for delivering swimming and water safety content (Field et al., 2022). To address these challenges, this paper offers suggestions by providing practical, dry-land activities PHE teachers can facilitate in their classrooms, gymnasiums, or outdoors.

Water Safety Activities and Content

The following three activities are designed to be facilitated on dry-land as many schools do not have regular access to aquatic facilities, and as per the barriers listed above, some teachers may not be equipped with skills, knowledge, and/or confidence to take students to aquatic environments. These activities are modifiable for K-12 students. The intention of these activities is to teach students important safety concepts associated with participating in and around blue spaces. These activities require commonly found equipment and can be modified to suit student age, ability, and location (i.e., classroom, gymnasium, outdoor field, supervised natural blue spaces).

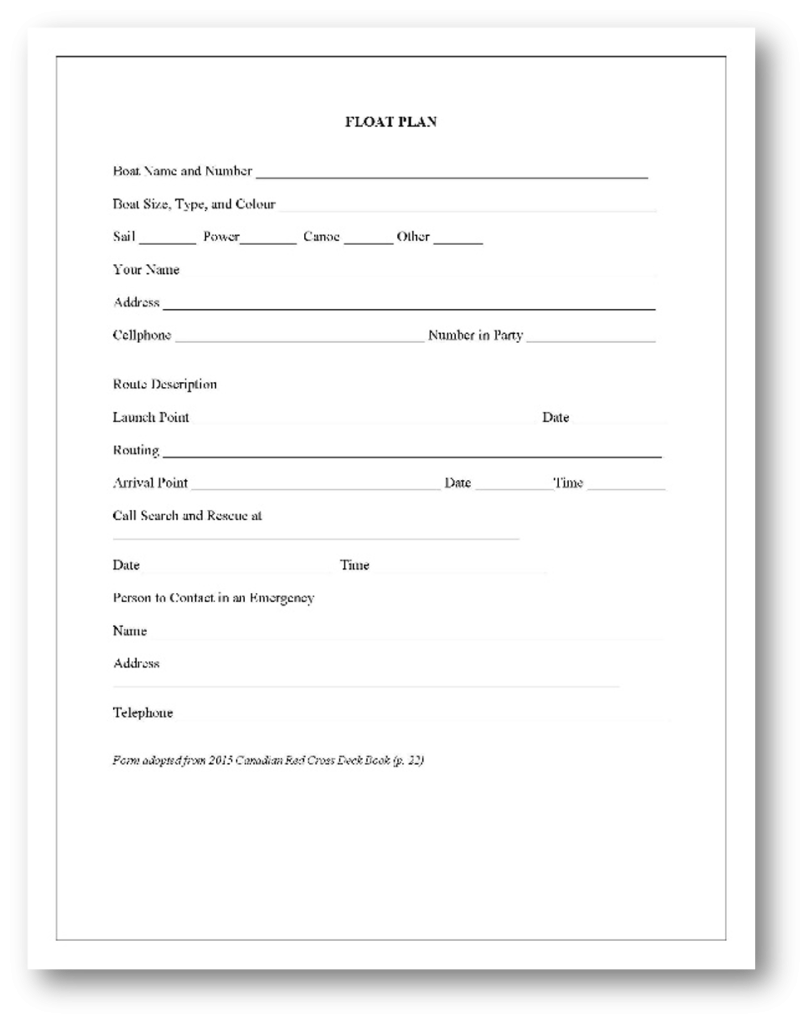

Activity #1: Safe Boating Preparation – Float Plans

- Overview for teacher: A float plan (also called a sail or trip plan) is a document or online form that is filed in preparation for a boating trip (i.e., fishing, kayaking, sailing). It includes basic information such as your destination, estimated departure and arrival time, and persons on board. In the event of an accident or emergency, a float plan can be used to direct rescuers to boaters in distress (Canadian Safe Boating Council, 2019). You can learn more about Float Plans here.

- Equipment: Flip chart paper, markers, float plan templates, variety of ‘boat building’ equipment (e.g., mats, blocks, cones)

- Group size: 2+

- Time required: 20 minutes

- Activity instructions:

- In teams, have students work together to build a boat out of the materials provided (can be large using gym mats, or small using construction paper or LEGO). This activity could incorporate physical activity if a time limit is set or materials are scattered around a gymnasium or outdoor location. Have students name their boat and encourage them to be as creative as they want.

- Gather students together and show a sample Float Plan (Sample Float Plan 1 Sample Float Plan 2). Provide students with a brief overview of what a Float Plan is, why it is important, and the information to be included on a Float Plan.

- Provide students with a piece of chart paper to create a float plan with the headings included in the sample Float Plans, or provide a blank printout of a Float Plan template to be filled in. Ask students to create the story of a journey they will be taking in their boat, and fill out their Float Plan with all of the relevant information (e.g., where they are going, how long they will be gone, who to contact if they do not return on time).

- Have students complete a gallery walk where groups visit each boat and the ‘owners’ of the boat present their boat and Float Plan.

- Review and discuss key aspects and importance of a Float Plan.

- If you wish to extend to Activity # 2, have students keep their boats intact.

Figure 1

A sample float plan template to provide students for Activity #1. Adapted from (Canadian Red Cross, 2015, p. 22).

Activity #2: Safe Boating Equipment (can be done as an independent activity or an extension of Activity #1)

- Overview for teacher: An important aspect of safe boating is ensuring boaters have the proper equipment on board to both prevent and respond to an emergency. These items can include properly fitting personal floatation devices (PFDs), flashlights, extra paddles, and sound signalling devices (e.g., whistles or airhorns) (Transport Canada, 2010). To prepare for a boating trip (including kayaking, canoeing, etc.), students should be familiar with these items. In particular, older students (Grade 6+), should be made aware of the dangers associated with substance use and boating, as alcohol is associated with over 40% of boating accidents (Canadian Red Cross, 2023a). More information on safe boating equipment and requirements can be found here.

- Equipment: Laminated cut-outs of safe boating equipment items; decoy items (i.e., a stuffed animal, alcohol – these items will change depending on the age group); boats from Activity #1, or substitute with plastic boats/pails; cones or other markers.

- Group size: 4+

- Time required: 15 minutes

- Activity instructions:

- Place laminated items around your space (e.g., classroom, gym, field, beach).

- Organize students into equal-sized groups and have each group line up behind a cone or other marker.

- On ‘Go’, have one student at a time from each group run out to collect a safe boating item and return to put it in the group’s boat.

- While group members are taking turns collecting items, the remaining group members can review the items that have been brought back. If they feel their team has selected any decoy items, they can return them to the play space one at a time with subsequent ‘runners’.

- Once all items have been overturned and selected, have each group present and explain the items they selected and why they are essential for safe boating.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2

Example of Safe Boating Equipment Items (Transport Canada, 2010) and Decoys for Laminating

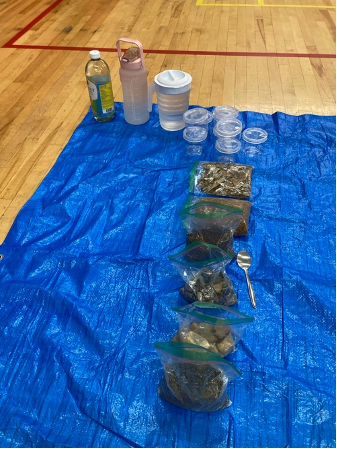

Activity #3: Safe Entries

- Overview for teacher: Unsafe entries (i.e., diving head-first into shallow water) are the leading sports-related cause of spinal cord injuries (Canadian Red Cross, 2023b). It is important to check water depth, search for underwater obstacles, and dive only in clear, deep water to prevent injury. Logs, stumps, and other underwater debris are present in many natural blue spaces. Currents, tides, and weather conditions can disturb debris and create unsafe entry conditions. Entering water feet first and checking for obstacles and safe water depth are important for preventing injury. More information about safe entries can be found here.

- Equipment: Empty, transparent plastic containers with wide-mount leakproof lids (to be able to fit debris inside; approximately 500mL to 1L); selection of naturally occurring items found locally (see instructions below); water jug to fill bottles, tarp or towels if completing activity inside.

- Group size: 4+

- Time required: 25 minutes

- Activity instructions:

- Have students go outside and collect rocks, sticks, pinecones, leaves, dirt, sand etc., that would fit into the containers you will be using. Make this a challenge by timing the activity, for example, “You have three minutes to collect five pinecones…”.

- Organize the class into small groups of 4-5. Ensure that each group has a container of water and an assortment of collected natural items. Have each group place a selection of materials into their container of water. Allow the items to settle on the bottom while you discuss with all groups about the different kinds of debris that can be found underwater in natural blue spaces.

- Seal and shake the containers so the debris is disturbed, and the water becomes murky. Adding a small amount of dirt or sand to mimic the sea/lake-bed can amplify the impact of shaking.

- Ask students what they noticed about the appearance of the water before and after the shaking. Discuss with students the importance of checking for underwater obstacles before entering the water as various weather conditions, currents, and tides can disrupt underwater debris and pose risk of injury. Reinforce the importance of feet-first entries for injury prevention.

|

|

Figures 3 and 4

Pre-service teachers being led through the Safe Entries activity

To feel prepared to implement the activities above, teachers may want to gain further knowledge and resources. Therefore, we have provided a list of additional resources in Figure 5.

| Lifesaving Society Canada Water Safety Activity Sheets for Kids |

| St. John Ambulance Water Safety Tips |

| Lifesaving Society Canada Water Safety Information and Tips |

| Transport Canada Safe Boating Guide |

Figure 5

Additional information and resources for implementing water safety activities and content in PHE

Conclusions and Future Recommendation

As participation in aquatic activities is an avenue to inspire students to be active for life, providing them with the knowledge on how to do so safely is important. This article presented three dry-land specific activities that teachers can use to educate students in PHE about water safety. With increasing recommendations to incorporate swimming and water safety content into public education, further resources for activities that students can participate in and around blue spaces are needed.

Acknowledgements:

We wish to acknowledge and thank Caytlyn Duke, a Bachelor of Physical Education student at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, for sharing her ‘Safe Entries’ activity for this paper.

References

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2016). Introduction to physical health and education. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/physical-health-education/introduction

Bryan, C., & Sims, S. (2020). Making a case for physical education teacher education as a viable degree program in colleges and universities. The Physical Educator, 77(4), 731-742. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18666/tpe-2020-v77-i4-9421

Canadian Red Cross. (2015). Red cross swim deck book. The StayWell Health Company Ltd.

Canadian Red Cross. (2023a). Boating safety. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://www.redcross.ca/training-and-certification/swimming-and-water-safety-tips-and-resources/swimming-boating-and-water-safety-tips/boating-safety

Canadian Red Cross. (2023b). Diving and safe water entries. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://www.redcross.ca/training-and-certification/swimming-and-water-safety-tips-and-resources/swimming-boating-and-water-safety-tips/diving-and-safe-water-entries

Canadian Red Cross. (2023c). Swimming lessons. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://www.redcross.ca/training-and-certification/course-descriptions/swimming-and-water-safety-courses/swimming-lessons

Canadian Safe Boating Council. (2019). Float plans. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://csbc.ca/en/float-plans

Davis, M., Gleddie, D. L., Nylen, J., Leidl, R., Toulouse, P., Baker, K., & Gillies, L. (2023). Canadian physical and health education competencies. https://phecanada.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/canadian-phe-competencies-en-web.pdf

Depledge, M. (2021). Forward. In S. Bell, L. E. Fleming, J. Grellier, F. Kuhlmann, M. J. Nieuwenhuijsen, & M. P. White (Eds.), Urban blue spaces: Planning and design for water, health and well-being (pp. xxvi–xxvii). Routledge.

Drowning Prevention Research Centre. (2022). Canadian drowning prevention plan, 9th ed. https://www.lifesavingsociety.com/media/370340/cdndrowningpreventionplan-en-9thedition-20220520.pdf

Ewing, R. (2010). Curriculum and assessment: A narrative approach. Oxford University Press.

Field, S. C., Gruno, J., & Gibbons, S. (2022). Blue spaces in physical and health education: A global review of curricular aquatic programs. International Journal of Physical Education, 59(2), 27-40.

Georgiou, M., Morison, G., Smith, N., Tieges, Z., & Chastin, S. (2021). Mechanisms of impact of blue spaces on human health: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052486

Giles, A. R., Pantano, S., & Khudadad, U. (2023). Fewer swimming lessons and lifeguard shortages make swimming even riskier this summer. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/fewer-swimming-lessons-and-lifeguard-shortages-make-swimming-even-riskier-this-summer-204086

Government of Northwest Territories. (2000). Physical education curriculum, kindergarten to grade 12. Retrieved July 10, 2024 from https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/sites/ece/files/resources/phys2000.pdf

Government of Ontario. (2019). Vision and goals of the health and physical education curriculum. Retrieved July 10, 2024 from https://www.dcp.edu.gov.on.ca/en/curriculum/elementary-health-and-physical-education/context/vision-and-goals

Grellier, J., White, M. P., Albin, M., Bell, S., Elliott, L. R., Gascon, M., Gualdi, S., Mancini, L., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Sarigiannis, D. A., van den Bosch, M., Wolf, T., Wuijts, S., & Fleming, L. E. (2017). BlueHealth: a study programme protocol for mapping and quantifying the potential benefits to public health and well-being from Europe's blue spaces. BMJ Open, 7(6), e016188. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016188

Lifesaving Society. (2023). Swim for life. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://www.lifesavingsociety.com/swimming-lifesaving/swim-program.aspx

Moffatt, F. (2017). The individual physical health benefits of swimming: A literature review. In A. Gates & I. Cumming (Eds.), The health and wellbeing benefits of swimming (pp. 8-25). Swim England. https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/health-and-wellbeing-benefits-of-swimming-report.pdf

Physical and Health Education Canada. (2024). Physical and health education curriculum in Canada. Retrieved July 10, 2024 from https://phecanada.ca/about/physical-and-health-education-curriculum-canada

Shingler, B. (2022). Across Canada, a shortage of lifeguards raises concerns about the next generation of swimmers. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/lifeguards-swimming-lessons-shortage-1.6519453

Smith, N., Georgiou, M., King, A. C., Tieges, Z., Webb, S., & Chastin, S. (2021). Urban blue spaces and human health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative studies. Cities, 119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103413

Stubbs, B., & Cumming, I. (2017). The wellbeing benefits of swimming: A systematic review. In A. Gates & I. Cumming (Eds.), The health and wellbeing benefits of swimming (pp. 26-43). Swim England. https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/health-and-wellbeing-benefits-of-swimming-report.pdf

Transport Canada. (2010). Mandatory safety equipment. Government of Canada. Retrieved July 7, 2023 from https://tc.canada.ca/en/marine-transportation/marine-safety/mandatory-safety-equipment

United Nations. (2021). General Assembly resolution 75/273 (Global drowning prevention). https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N21/106/27/PDF/N2110627.pdf?OpenElement

Vitale, V., Martin, L., White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., Wyles, K. J., Browning, M. H. E. M., Pahl, S., Stehl, P., Bell, S., Bratman, G. N., Gascon, M., Grellier, J., Lima, M. L., Lõhmus, M., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Ojala, A., Taylor, J., van den Bosch, M., Weinstein, N., & Fleming, L. E. (2022). Mechanisms underlying childhood exposure to blue spaces and adult subjective well-being: An 18-country analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101876

World Health Organization. (2014). Global report on drowning: Preventing a leading killer. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-report-on-drowning-preventing-a-leading-killer

World Health Organization. (2017). Preventing drowning: An implementation guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511933

World Health Organization. (2021, April 27, 2021). Drowning. Retrieved June 27, 2023 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning