Exploring Teachers’ and Parents’ Perceptions of, and Experiences Using, Strategies to Improve Physical Activity for Children with Exceptionalities

Previously published in Volume 87, Issue 4

Abstract

Children with exceptionalities are participating in physical activity less than children without, and as a result, are overweight, less physically fit, less motor proficient, fatigued, and feel more pain. The objective of the current study was to examine the specific strategies educators and parents used to involve children with exceptionalities, particularly children with a learning disability, intellectual disability, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and autism spectrum disorder, in physical activity to better support their health and well-being. A basic interpretative qualitative research approach was used to explore the research question: What strategies have parents and educators used to engage or encourage children with exceptionalities to improve their involvement in physical activity? Three teacher and seven parent participants were recruited and interviewed. Five major themes were purposively selected: (1) “It helps everything”: Improving children’s health and well-being; (2) “Knowing what makes them tick”: Valuing relationships; (3) “Breaking down barriers”: Providing verbal support and feedback; (4) “Tapping into what they enjoy”: Finding and promoting physical activities children enjoy; and (5) “Different opportunities”: Providing access to physical activities. These themes, and the implications of these findings and proposed future research directions, are discussed.

Introduction

Different forms of moderate to vigorous physical activity can have a significant impact on children’s health and well-being including cognitive development, physical, mental, and emotional health, social relationships, and well-being (Bell et al., 2019; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2013; Pan, 2010; Pastula et al., 2012). It is difficult to engage all children in regular physical activity due to factors such as high rates of obesity and inaccessibility (i.e., lack of appropriate facilities/equipment, motivation, and/or education about benefits physical activity; Hwang & Kim, 2013). While physical activity is key to the health and well-being of all children, it is even more essential for children with various exceptionalities (e.g., Chang et al., 2012). Yet, children with exceptionalities are not engaging in physical activity as frequently as other typically developing children (e.g., Carlon et al., 2013) resulting in a higher prevalence of obesity (Chen et al., 2010). It is the influential people in children’s lives such as educators and parents who understand physical activity enhances the health and well-being in children of all abilities (Rodrigues et al., 2018; Rudella & Butz, 2015), to encourage and support children to be more physically active.

A limited number of specific strategies have been identified and studied to determine if they do, in fact, promote all children to engage in physical activity (e.g., Jensen, 2006; Mowling et al., 2004). Physical activity is important for all children (e.g., Fedewa & Ahn, 2011), including those with exceptionalities (e.g., Chang et al., 2012; Pastula et al., 2012). However, there is limited current research exploring how adults are engaging children, particularly those with exceptionalities, in physical activity (e.g., Beets et al., 2010; Rodrigues et al., 2018), and it is evident these strategies are not always effective in consistently engaging children.

If we understand physical activity affects numerous aspects of children’s health, particularly those with exceptionalities, then it is important to explore the strategies educators and parents use to engage them. This study explored the strategies parents and teachers used to engage or encourage children with exceptionalities to improve their physical activity involvement.

Methods

Upon approval of the University of Saskatchewan’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (# 1401), purposive sampling recruited 10 participants, seven teachers and three parents, in a large urban centre in Western Canada who: were 18 years of age or older and willing to share their experiences engaging children in physical activity; and had a child and/or a child in their class aged 5-17 years of age diagnosed with learning or intellectual disabilities, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and/or autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

A basic interpretive qualitative approach was used to learn how individuals experience and interact with their social world, as well as the meaning it has for them (Merriam, 2002). Data was analyzed cyclically using five phases: transcription, description, analysis, interpretation, and display (Brenner, 2006). Inductive analyses were emphasized, and themes purposively selected, that strongly linked to the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006) using the theoretical frameworks of attachment theory (Bowlby, 1958), endorphin theory (Sandman 1990/1991), theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1985), and social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986) as lenses. All participants reviewed and signed a consent form before participating in the study that outlined the purpose of the study, participant’s rights (i.e., right to withdraw), and how confidentiality would be addressed (i.e., use of pseudonyms). As data collection for this study took place before and during the pandemic, initial and follow up interviews were conducted both in person and later online to ensure the health and safety of all. In addition, the researcher was mindful of the sensitivity of the research topic for parents and teachers associated with children with exceptionalities and gauged and responded to their emotional and psychological states during data gathering discussions (i.e., explored/followed up on key points in more/less depth, shortened/lengthened interview sessions as needed).

Findings

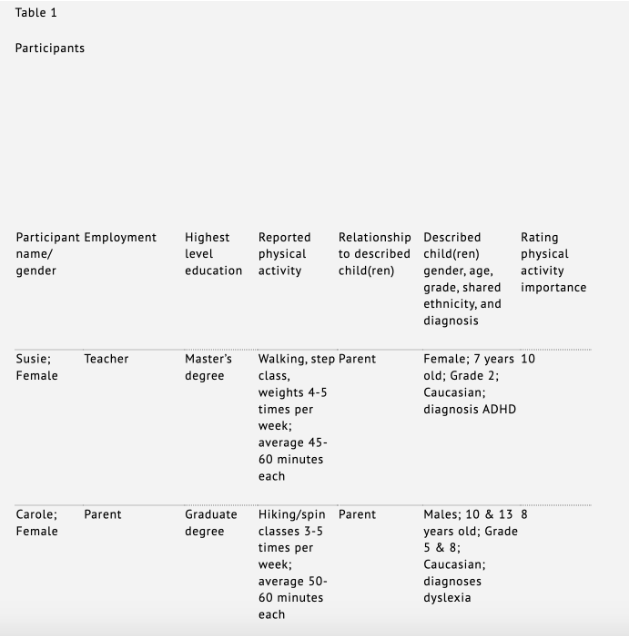

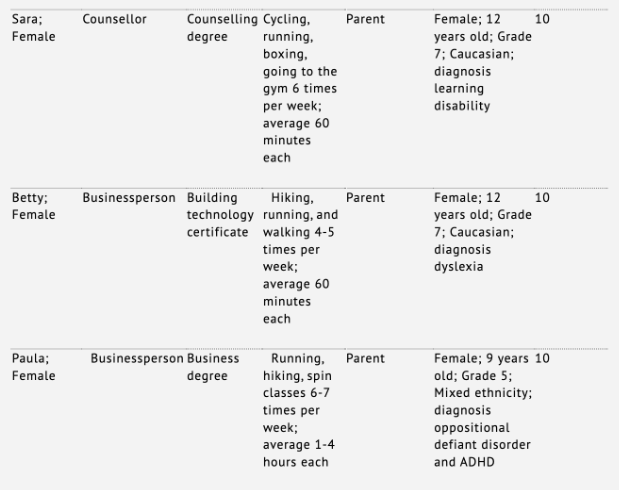

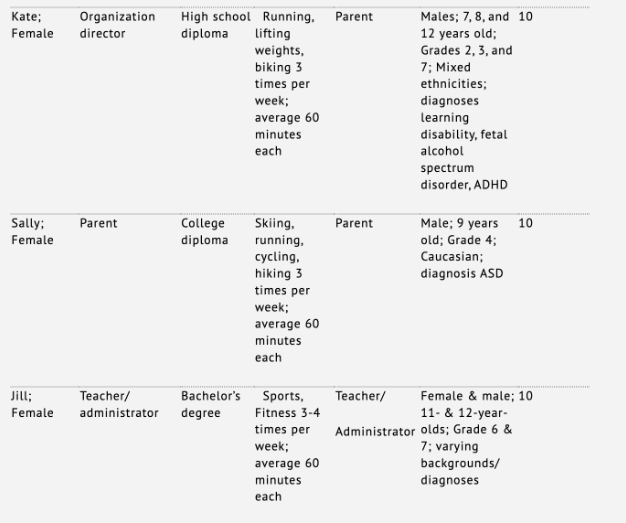

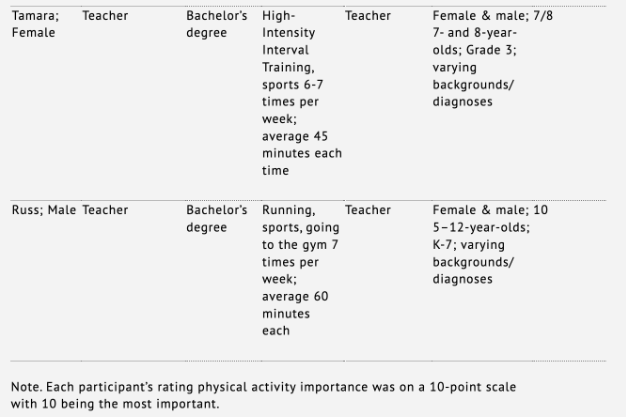

Participants described themselves and rated the importance of physical activity for their child/children in their class on a scale of 1-10, with 1 being the least important and 10 being the most important (see Table 1).

Participants shared similar viewpoints regarding the benefits of physical activity, and their different experiences/examples of specific strategies used to engage children, adding to the uniqueness, authenticity, and depth of the study. Five major themes emerged.

Theme 1: “It Helps Everything”: Improving Children’s Health and Well-Being

Most participants mentioned indicators of health and well-being when discussing children who were active prior to and within learning. Parent Kate noticed a better/faster rate of learning when a child engaged in physical activity while learning. She shared:

"It’s a great way for them to learn when they’re moving their bodies, especially kids with ADHD… It’s their way of learning, when sitting down at a table doesn’t work… you can be creative… they get to move their body, whether that’s hopscotch or hitting a ball against the words, they learn much faster."

Physical participation benefits were also reported. Susie noted, “it is important for their physical health… their heart and lungs and also just for weight regulation, building muscle and having a psychologically healthy attitude to exercise.” The knowledge of physical activity having positive effects on their bodies was enough to have them participate. As Sara reported after her daughter participates in physical activity, “she tends to sleep better and be more tired at the end of the day.” Participants also frequently mentioned social relationships developed through physical activity as a key benefit for children choosing to participate in certain activities because their peers were involved. Jill divulged:

"It’s huge for their social development…Physical activities involving interacting with peers helps build their confidence and sense of belonging, in turn, producing better work."

Mood and regulation were other factors noted by both parents and teachers as directly correlated to physical activity. Betty disclosed:

"They’re just so much happier when they’re active, even if it’s just outside… because you’re getting antsy… they go outside and then they come in, they’re just more even keeled."

Theme 2: “Knowing What Makes Them Tick”: Valuing Relationships

Participants reported adult and peer participation and understanding/building rapport were key to engaging children in physical activity. If parents and teachers engaged in the physical activity themselves, children were more likely to engage. Kate reported, “the biggest strategy is participating with them. Or having friends participate with them… get them involved… actually do the activity too.” Similarly, if children’s peers were involved, they were more likely to want to participate. Sara noted, “A lot of the activities she does are also social, that’s often a motivator for her.” Understanding each unique child allows for select physical activity engagement strategies to be employed. Moreover, if rapport was built with the child, they would likely be more receptive to participating in physical activities. Tamara stated:

"If I’m taking them out for a quick game…[and] I know they don’t like certain games, for instance, dodgeball… but the rules are just a little bit too much so, I’ll try and make sure…I want an inclusive attitude in my classroom."

Theme 3: “Breaking Down Barriers”: Providing Verbal Support and Feedback

Participants also shared emphasizing achievements, explaining the benefits, expecting engagement, and using encouraging words and actions as physical activity engagement strategies. For example, Kate disclosed it’s about, “always recognizing how far they have come versus where they came from.” A child was able to feel like they were achieving success and more willing to participate in the physical activity again if words and/or visuals showing progress were provided. Explaining the benefits of physical activity to the child was also helpful. Carole explained, “We pushed running because I know it helps relax the mind and I try to explain that to him…I’ve been pushing the link between how he feels afterwards, and he does feel better after.” Expecting the child to participate in the physical activity also helped to engage them. Teacher Russ used this tactic with students, sharing: “…I teach them in gym class there’s not much of a choice. This is what we’re doing, the whole class is doing it…sometimes you have to do things that are not your favourite.” Finally, the strategy of using words of affirmation and encouragement pertaining to the child’s participation in the physical activity was used. Kate shared, “It’s more just cheering them on in any moment of success they have, whether it’s just riding their bike or doing a jump.”

Theme 4: “Tapping Into What They Enjoy”: Finding and Promoting Physical Activities Children Enjoy

Participants expressed fostering what children love to promote physical activity engagement. Carole stated, “My son doesn’t enjoy swimming lessons or very formal training. If it’s much more play based, playing tag, climbing on apparatuses…then yes, he absolutely enjoys it.” Finding out and honouring what physical activities the child liked was key to having them participate in it again. Tamara revealed with her class, “Sometimes the physical times are the times they can shine and be themselves and be happy with their friends because that’s an area they have a strength.” Participants also commented on the need to emphasize movement rather than a particular activity. Sara shared if her child “…doesn’t want to do something…like a specific exercise, then we’ll do something else… For example, if it was a cardio thing and she didn’t want to run, then we would do something else.”

Theme 5: “Different Opportunities”: Providing Access to Physical Activities

Participants shared that providing opportunities for everyone, modifications, and incorporating physical activity into the academic classroom were ways to engage children in physical activity. Incorporating physical activity right into their classroom makes it more accessible and provides modifications within the specific physical activity. Russ shared as a teacher, “The first thing I always do is, whenever I’m doing a unit or lesson, I start with something they’ll all be able to do successfully… something very, very basic within that skill. If it’s throwing and catching, it could be just throwing the ball to yourself and catching it, or bouncing it to yourself, so they can just even explore and feel and try.” Catering to a child’s unique strengths and needs and allowing access to each activity through modifications, such as through equipment or specific movements, was key to their success. As a parent and a teacher Susie explained:

"Her gymnastics’ teachers seem to sort of take the activity level down to where she is…With swimming, when the other kids have progressed to being able to float independently, the instructor gives her a pool noodle or a floaty thing she has to hold in her hands."

It is important to ensure each child can fully participate in physical activities.

Implications, Strengths, and Limitations

This research highlighted both parent and teacher perspectives on physical activity and strategies being used to engage children with exceptionalities. Allowing participants to share their personal successes and challenges gives others the opportunity to see themselves in their stories and consider how they could better involve children in physical activity. This study also adds to existing research. In theme 1, improving children’s health and well-being, participants illustrated the importance of engaging children in physical activity for cognitive, physical, social, mental and emotional benefits as has also been outlined in existing research literature (e.g., Bell et al, 2019; McMahon et al. 2019; Nakutin et al., 2019; Wilk et al., 2018). All people working with children should be encouraging them to be engaged in physical activity to reap its benefits. Furthermore, the strategies participants reported in theme 5 related providing access to physical activities broadened existing ideas in the research literature (e.g., Norris & Columna, 2016; Walker et al., 2019) by suggesting that opportunities and modifications to support children’s physical activity engagement needed to be provided for everyone. Perhaps most importantly, participants reported specific engagement strategies for children with exceptionalities that have only been explored in limited previous studies such as the recognizing the value of relationships in promoting physical activity in theme 2 (e.g., Davis et al., 2010), the importance of providing verbal support and feedback in theme 3 (e.g., Beets et al., 2010), and finding out what children enjoy in theme 4 (e.g., Rudella & Butz, 2015). The findings in this study can further help educators, parents, and the public understand the importance of engaging all students in physical activity and highlights some specific supportive strategies they can employ moving forward.

However, while this study used an appropriate sample size, incorporating additional participants in future studies who are from rural or northern areas, male, non-binary, and/or from more diverse cultural backgrounds and adding questions considering additional factors that may be influencing participants’ perspectives and decisions such as their age, may highlight additional views related to physical activity and engagement strategies being used.

Conclusion

Parents and teachers shared their perceptions of the benefits of physical activity and the specific strategies they have found useful in engaging their child(ren)/students with exceptionalities in physical activity resulting in five major themes being purposively selected: (1) “It helps everything”: Improving children’s health and well-being; (2) “Knowing what makes them tick”: Valuing relationships; (3) : “Breaking down barriers”: Providing verbal support and feedback; (4) “Tapping into what they enjoy”: Finding and promoting physical activities children enjoy; and (5) “Different opportunities”: Providing access to physical activities.. The personal stories shared by participants allows others to consider how they could better engage children with varying needs in physical activity.

References

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhi & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11-39). Heidelberg: Springer.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Beets, M., Cardinal, B., & Alderman, B. (2010). Parental social support and the physical activity-related behaviours of youth: A review. Health Education & Behaviour, 37(5), 621-644.

Bell, S., Audrey, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, A., & Campbell, R. (2019). The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: A cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16, 138.

Bowlby, J. (1958). The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 39, 350-371.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Brenner, M. (2006.) Survey methods in educational research. In J. Green, G. Camilli & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 357-370). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Carlon, S., Taylor, N., Dodd, K., & Shields, N. (2013). Differences in habitual physical activity levels of young people with cerebral palsy and their typically developing peers: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(8), 647-655.

Chang, Y., Liu, S., Yu, H., & Lee, Y. (2012). Effect of acute exercise on executive function in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 27(2), 225-237

Chen, A., Kim, S., Houtrow, A., & Newacheck, P. (2010). Prevalence of obesity among children with chronic conditions. Obesity (Silver Spring), 18(1), 210-213.

Davis, K., Hodson, P., Zhang, G., Boswell, B., & Decker, J. (2010). Providing physical activity for students with intellectual disabilities: The motivate, adapt, and play program. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 81(5), 23-28.

Fedewa, A. & Ahn, S. (2011). The effects of physical activity and physical fitness on children’s achievement and cognitive outcomes: A meta-analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82(3), 521-35.

Hwang, J., & Kim, Y.H. (2013). Physical activity and its related motivational attributes in adolescents with different BMI. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 20(1), 106-113.

Jensen, E. (2006). Enriching the brain: How to maximize every learner’s potential. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, A John Wiley & Sons Imprint.

McMahon, D., Barrio, B., McMahon, A., Tutt, K., & Firestone, J. (2019). Virtual reality exercise games for high school students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Special Education Technology, 35(2), 87-96.

Merriam, S. B. (2002). Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mowling, C., Brock, S., Eiler, K., & Rudisill, M. (2004). Student motivation in physical education: Breaking down barriers. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 75(6), 40-45,51.

Nakutin, S., Gutierrez, G., & Campbell, J. (2019). Effect of physical activity on academic engagement and executive functioning in children with ASD. School Psychology Review, 48(2), 177-184.

Norris, M. & Columna, L. (2016). Physical activity experiences of families of children with visual impairments. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 87, 1.

Pan, C. (2010). Effects of water exercise swimming program on aquatic skills and social behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 14(1), 9-28.

Pastula, R., Stopka, C., Delisle, A., & Hass, C. (2012). Effect of moderate-intensity exercise training on the cognitive function of young adults with cognitive disabilities. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(12), 3441-3448.

Rodrigues, D., Padez, C., & Machado-Rodrigues, A. (2017). Active parents, active children: The importance of parental organized physical activity in children’s extracurricular sport participation. Journal of Child Health Care, 22(1), 159-170.

Rudella, J. & Butz, J. (2015). EXERGAMES: Increasing physical activity through effective instruction. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 86(6), 8-15.

Sandman, C. (1990-1991). The opiate hypothesis in autism and self-injury. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 1(3), 237–248.

Walker, A., Colquitt, G., Elliott, S., Emter, M., & Li, L. (2020). Using participatory action research to examine barriers and facilitators to physical activity among rural adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(26), 3838-3849.

Wilk, P., Clark, A., Maltby, A., Tucker, P., & Gilliland, J. Exploring the effect of parental influence on children's physical activity: The mediating role of children's perceptions of parental support. Preventative Medicine, 106, 79-85.

Table 1: